On the sunny Friday before Memorial Day, evil came to my little town of 6,000.

A Willington man who lived just down the road, in a woodsy neighborhood my son played in, was murdered. He had offered a ride on his quad to a 23-year-old stranger who had left his motorcycle down by the cul-de-sac.

Then something went very wrong. The Good Samaritan was attacked – allegedly by a sword-wielding university engineering student who knew someone on the dead-end road. An elderly man was critically injured as he ran to his neighbor’s aid. And the suspect fled on his motorcycle – off on a spree of murder, home invasion and kidnapping that led to a multistate manhunt and his capture six days later.

I didn’t know about the crimes down the road until hours afterward, when official reports began to emerge. Then, at some point in the day, I learned the murder victim was someone I knew: Ted DeMers, a talented furniture artisan I once interviewed about his art for a local cable TV show.

In the next few days, swamped by a gush of public interest in the killer, I wanted to remind myself of Ted. I dug out my copy of the 2009 interview and watched it again.

“I’m a woodoholic,” he joked, during the videotaping for “Artists and Authors.”

He spoke warmly about his love of his medium and schooled me about the patience it takes to make pieces the way he did. He credited his wife, Cyndi, with supporting his dream to open a business in their basement, and also with keeping him on track as his partner. “She’s not afraid to tell me when I’m going the wrong way on something,” he said.

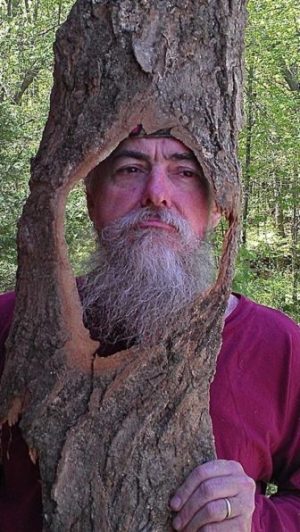

He told me that he would look at a tree until he pretty much saw what it had to offer as a piece of furniture.

“I like to let the wood do what it’s going to do,” he said.

And that involved quite a process. He would select the right tree, oversee how it was cut up at his nephew’s sawmill in Eastford (“each board is a prize”), let the wood dry naturally for three to five years and wait its turn for the right design.

He made a piece of furniture from the wood off the same tree, using traditional hand-planing, so he could hear his Western music without machine noise interference. Plus, he could avoid sandpaper and give the figuring a crisper look. He drew on his early training from a couple of “outrageous older gentlemen” who taught him cabinet making and finishing when he was a young man.

His goal was always a “close tolerance” – no seams, tight joints, looking like it’s all one and just right.

In recent years, after pursuing the close tolerance for so long, successful at shows, winning awards, doing his best work, Ted was ready to claim to Cyndi, “I guess I can call myself a furniture maker now.”

But, abruptly, his life, at age 62, was interrupted by the attack on Mirtl Road.

The University of Connecticut senior, Peter Manfredonia of Newtown, is being held on $7 million bail and is pleading not guilty to charges of murder, attempted murder, assault and kidnapping in the Willington crimes. One of those involved a rural home invasion, where he allegedly bound and held the cool-headed homeowner for about 24 hours in his basement and helped himself to supplies, weapons, cash and a truck he drove to Derby. Manfredonia is also the suspect in the murder of his former high school classmate, Nick Eisele, 23, in Derby.

I’ve lived here 23 years, a newcomer by Willington standards, but I know my town is changed forever, despite its people’s mettle. Before this, the most disturbing episode was a 1998 shootout on the northern edge of town between three state troopers and a postal worker with an arsenal in his trailer. All four were injured, and the troopers required surgery.

Normally, Willington leans into its Quiet Corner image, with stunning scenery on the back roads and a sloping, Yankee town green capped by the 19th century Old Town Hall. People still meet there to decide on whether to buy a new snowplow or allow live entertainment in town. (I’m not kidding.) But, just a few minutes south is Connecticut’s flagship university on a campus the size of a small city. Willington shelters some UConn faculty and students – and Hartford commuters – who crave a slower pace and fresher air, and others who work locally as farmers, small business employees or entrepreneurs, like Ted.

Back in the studio, the half-hour went fast. I remember Ted’s clear eyes and his kind face, a gentleness coming from a mountain man. I loved hearing him talk in detail about each slide he showed of his pieces. “I covet that one,” I blurted on camera, when he showed a slender cabinet rendered from ribbon red maple and cherry. “My wife had her eye on that cabinet, but it went,” he said, hinting at the sacrifice of making art for a living.

Years later, when I led the unWillington grass-roots effort to keep our town from being dwarfed by an outsized state firearms facility slated for the center of it, Ted offered a few of his distinctive cutting boards for a silent auction. I was touched by his quiet support. I have one of those boards in my home, but I find I don’t really want to cut on it and mar its smooth beauty. I know that Ted might not approve, that he made his art to be used, and often. But I think he’d forgive me.

He had discipline and adhered to a creed, as a former Marine, father of two sons and traditional woodworker, but he deferred to the natural world when it came to letting trees, and people, be what they were meant to be, warts and all.

“There’s just endless amounts of trees with imperfections out there waiting to come to the shop,” he said, about the potential for making distinctive pieces. “I used to have to go out to the customer’s house and explain to them, ‘It’s wood. You know, it’s wood. And you get things like that.’ Now, people are desiring imperfections.”

He sums up: “I haven’t found a piece of wood yet that I wouldn’t want to use.”

On Memorial Day weekend, Willington came out and grieved together in the middle of a pandemic that paled by comparison. Folks who knew Ted – and many who didn’t – organized a GoFundMe campaign for the family, invited townspeople to set out decorated candles around the town green for two nights, and, with family approval, created a Drive-by Wake “Ted Style” a week after his death.

After all this, I know more about the rest of Ted. Husband of 42 years. Dog lover. Expectant first-time grandfather (“Teddy” was born June 23). Blue-ribbon neighbor.

His son, Chris, wrote in a tribute that everyone wanted to be on the little league team Ted coached because he was a hard-ass with a light heart and, as a school trip chaperone, slightly reckless.

The kind of a guy who harbors a small town’s soul.

We don’t fully know the story of what happened when evil came to Ted’s woods. But I have this persistent sense that, a former Marine, a man who can see into the being of a tree, knew what was afoot and acted heroically to save the others in his woods.

Late in the interview, Ted told me his company’s name was Everlasting. “I give an everlasting warranty. The warranty’s forever,” he paused, “except it’s my lifetime.”

Stephanie Summers, a freelance editor in Willington, was a longtime editor at The Hartford Courant and the former Northeast magazine.