The sun gleamed through the windows of Wise Guys Scissor Society barbershop in downtown Hartford as a barber brushed the trimmings from Eriberto DeLeon Jr.’s cape.

DeLeon glanced at the mirror, taking in his freshly groomed goatee as he rubbed his fingers along his stubbled chin.

“I look clean, man,” he said with a smile.

This cut … well, it was special.

For 52-year-old DeLeon, the haircut marked his first professional cut in over three decades.

DeLeon was released from Cheshire Correctional Institution in April 2024 after serving just over half of his 60-year sentence for felony murder.

Glancing at the skyscrapers and newly built lofts that make up Hartford’s skyline today, DeLeon pointed out areas that have changed since he last walked those streets in 1991.

“None of this was here,” he said, pointing to restaurants and cafes.

DeLeon has changed, too.

No longer a 19-year-old looking for money, success and family in all the wrong places, DeLeon is now looking to the future with an eye toward building his credit, applying for jobs and doing well in college, which he enrolled in within months of his release.

Eventually, he made his way down to Wellington Street, a place where young DeLeon spent many of his teenage years. DeLeon lived nearby, on the D-Side of Charter Oak Terrace, a housing project in Hartford that gave families access to affordable housing, until it was torn down in 1996.

As DeLeon stood for a moment gazing at the abandoned lot with a feeling of nostalgia, he recalled how the area once looked.

“When I came out and visited this area, I was surprised because there used to be buildings all along this street. Now it’s all abandoned,” he said. “It’s crazy because some of these same areas were places we would hang out, sell drugs and just run the streets here when we were younger.”

Chameleon

At 13, DeLeon was introduced to the sometimes unforgiving and brutal streets of Hartford. He started out by stealing cars, shoplifting and skipping school.

“Sometimes I would steal cars and car stereos with my buddies just because,” said DeLeon.

A year later, he would find himself affiliated with a street gang. DeLeon said that the gang began to recruit him after noticing how he carried himself and that he wasn’t fearful.

For DeLeon, the life he lived during the evening when he went home was nearly the opposite from the life that some of his peers might have known him for.

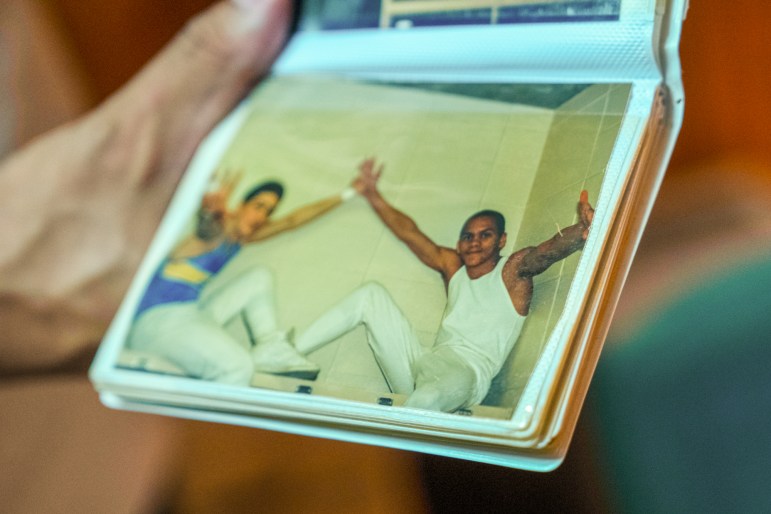

A skilled competitive swimmer, he competed with the Pope Park Swim team. He said he dominated against high school swimmers in the backstroke and freestyle as a middle schooler.

After being sent to an alternative school, Connecticut Junior Republic, due to his behavioral issues at 16, DeLeon became a three-sport varsity athlete in swimming, gymnastics and basketball. The 6-foot-2 athlete broke a number of school swimming records.

“There were a lot of meets where I would get first,” said DeLeon, looking back at some of his old swimming medals from CJR in his aunt’s basement.

Unlike many talented varsity athletes, DeLeon didn’t have ambitions to compete in college.

“People back then didn’t really see swimming as a way to get out of the ‘hood,” said DeLeon.

“I was like a chameleon and had to adapt to the environment around me,” DeLeon said, noting that he’d spend the afternoon at the pool but then would go home and see violence and drugs.

DeLeon was raised by his grandmother, aunt and grandfather. His grandfather served as a father figure until he died when DeLeon was 11. Years later he would also lose his uncle to an overdose.

“I tried to do the best I could do, since I knew he didn’t have his mother around,” said Montanez, DeLeon’s aunt, who at 22 served as a mother figure.

DeLeon recalls seeing his biological mother about two times during his lifetime. He remembers thinking that his grandma was his mother.

“But you know, I don’t have any resentment towards her, nor my dad. They had me when they were young, and who am I to point the finger?” DeLeon said.

“Sure, I could say that not having my mom nor dad played a role in the decisions I made, but I also have to take some of my own responsibility,” said DeLeon.

He searched for a sense of family in the streets.

“The streets were a different type of family,” he said.

Between the ages of 16 and 19, DeLeon’s fast-paced lifestyle of violence and criminal activity began to afford a life of luxuries and power.

Life would never be the same

In 1992, the year DeLeon’s life changed forever, the average price of gasoline was $1.13 a gallon, the Olympic men’s basketball “Dream Team” won gold for the United States, Arthur Ashe won sportsman of the year, IBM announced the idea of a smartphone and Google didn’t exist.

Many 20-year-olds during this time were fixated on their beepers, prepping for college and sporting stonewashed denim overalls or the Starter jacket of their favorite sports team. Twenty-year-old DeLeon instead found himself standing in front of a judge in a Hartford courtroom.

DeLeon’s aunt, Anna Montanez, recalled the tears streaming down her face as she witnessed the little kid she helped to raise taken away in shackles for what she thought would be forever.

DeLeon was sentenced to 60 years for his role in the death of a Glastonbury homeowner in a home invasion.

“I thought my life was over,” said DeLeon, sitting in his aunt’s basement, recounting the day of his sentencing.

The day that led to his sentencing was one he didn’t think would end the way it did, he said.

“At the time when we broke into the house, I wasn’t thinking about whether this guy was dead or not when we fled the scene,” said DeLeon. “This was a house we had robbed before, and I just thought we would take the safe without him being home and leave, but it didn’t end up happening like that, unfortunately.”

DeLeon would spend his 20s, 30s, and 40s all behind bars, missing out on the pivotal moments of adulthood.

“For years during my incarceration, I tried to hide my emotions,” he said. “As time went on, I realized, yeah, there are some things I missed out on.”

Back to the basics

In the months following his release, DeLeon moved into his aunt and uncle’s three-bedroom home, where he plans to live until he can save enough to get his own apartment.

He also got a job working at the Full Citizens Coalition, a Hartford nonprofit that gives formerly incarcerated individuals employment and access to resources.

But one summer morning last year, he went to an appointment with his caseworker Amy Arroyo and told her about a new job he planned to apply for.

“Oh wow, Eddie, I’m so proud of you,” she said.

Other days, he takes advantage of so-called luxuries he didn’t have while incarcerated.

Proper dental care is new to him, for example.

Months after his release, he sat in a dental chair unfazed by the root canal procedure that many might consider painful.

“This is better dental help than in prison, because in prison, if you complained about having toothaches or dental issues, they would just pull the tooth,” said DeLeon, who had a grin on his face as he left the dental office after his procedure.

Living large

In his teens, DeLeon lived a more lavish lifestyle.

The more status he began to obtain, the more the power got to his head, he admitted.

“Now, you’re the lead actor, and you must worry about how to sustain this lifestyle. You know, my fingers were filled with diamonds and gold rings,” said DeLeon. “I began to think you can’t really tell me anything.”

“I remember right when I had got out of juvie, I had pulled up to the gas station in a shiny jet-black Pontiac Trans Am with gold rims. I remember one of the kids in the neighborhood had stopped me, and he was looking at my car like, ‘Dang, man, what did you do to get that?’” said DeLeon.

Looking back, DeLeon realizes the lifestyle he was leading could have led to a worse ending to his life story.

“But I knew that if I was to remain home carrying on like I was, I probably would have eventually ended up dead or killed because of the stuff I was doing.”

Wrong direction

DeLeon said he has learned from his mistakes, but for his first 15 years in prison, he continued many of the same bad habits he was accustomed to in the outside world.

While awaiting trial and before even stepping foot into state prison, DeLeon became initiated into the Latin Kings gang.

“I joined largely for a sense of fraternity and community,” he said. “When you’re in jail, sometimes you just have a survive by any means mentality.”

He said he accumulated more than 11 infractions in his first eight years incarcerated.

“When I first went to prison, I used to like going to segregation because I could just pass time. It wasn’t until after some years where I started to realize how bad being confined to a small box is for your mental health,” DeLeon said. “It’s really not a good place.”

“I hate to say it, but the streets had trained me for prison, and it wasn’t too hard for me,” said DeLeon. DeLeon noted that there were things he would see in prison that just became normal, like seeing people stabbed or hit in the head with combination locks and sitting in a pool of their own blood.

Selling contraband and being a top leader in his unit, DeLeon found himself having a sense of power similar to that of when he ran in the streets of Hartford. However, as he entered his 30s, he knew it was time for change.

Risky decision

He began to notice that he was getting older, but the people coming in were only getting younger. “I got tired of being tired of the same old stuff,” he said.

Around 2007, he had a meeting with one of the top Latin Kings leaders in his facility, stating that he would be giving up his colors and departing from the gang.

“I knew that there could be repercussions, because even though he could tell me, ‘Oh yeah, you’re good,’ and I got the green light to leave, the next thing you know, you’re hit up, but I got lucky — that never happened to me,” said DeLeon.

It was during this time that the then-32-year-old began to develop a desire to grow. “My main goal was to get through this bid without getting jammed up. I still had the mindset that I would live through the 60 years,” said DeLeon.

DeLeon became a mentor and source of wisdom for the younger generation, teaching them what to do and what not to do. He even found that some of the younger Latin Kings members would come to him for advice on how he managed to get out of the gang.

Then, on April 3, 2024, for the first time in over three decades, DeLeon would get to experience life as a free man after being granted commutation for good behavior and advocacy work behind bars. Not stuck on parole, probation or facing any other stipulation, DeLeon could get his life back.

30 years later

These days, DeLeon is still getting used to the crowds on public buses and learning how to use his smartphone to get around.

On his way to a credit union one day, he referenced the Google Maps app to make sure he was headed in the right direction.

Once he arrived at the Bloomfield community credit union, DeLeon waited in line before hearing one of the personal bankers call his name. As he sat down at the bank staffer’s desk, she asked for his information and ID.

“Yeah, I never applied for a credit card before,” he said with a smile.

She looked at DeLeon with a smile on her face as well, but also a look of confusion.

He explained his backstory to the woman and she followed up with words of praise and encouragement.

After a briefing on the credit card guidelines, DeLeon explained how he planned to manage his savings and build up his credit. “Next I’ll be able to save up and buy my own car eventually,” he said.

New era

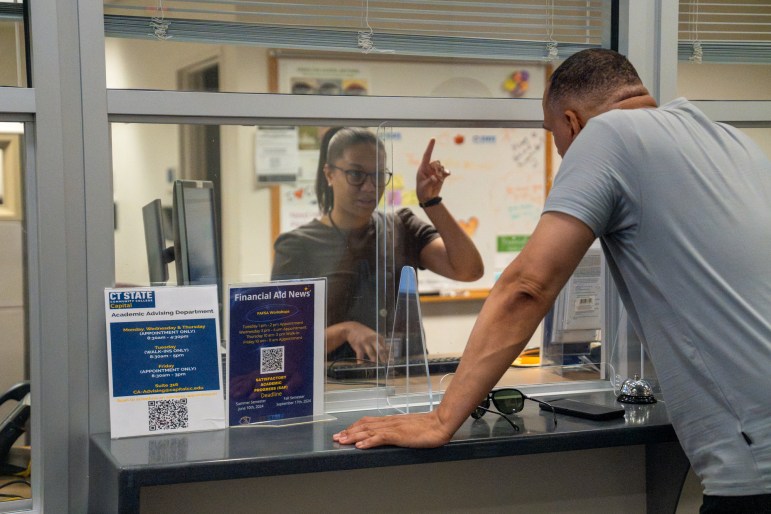

One of his first decisions upon his release was to enroll in college. He wanted to start as soon as the fall of 2024.

The idea of enrolling in college was something that would have never crossed DeLeon’s mind 30 years ago. But as he entered the silver doors of Capital Community College, he knew his enrollment was more meaningful than just registering for classes or getting a degree to help him get a good job. This moment was one of resurgence and rebirth.

As he talked to the person behind the desk at the college, the topic of his incarceration came up. “I served 30 years in prison,” DeLeon said.

She looked at him with shock before taking a pause to congratulate him.

Later, DeLeon notes that he has changed in the three decades he spent behind bars, and so have his reasons for moving forward.

“You know, I’m not the same person I was when I went in. My motivation is different,” he said. “When people search up my name, do I want the first thing to come up is my name being associated with murder? Or do I want it to be that this individual has made positive impacts in so many areas?”

He sat in the basement of his aunt’s house, sifting through the sheets of his notebook, prepping for a job interview as an advocacy coordinator for incarcerated individuals. This job was a big deal, DeLeon said.

The job would not only be a great financial help — allowing him to purchase a car and an apartment — but would allow DeLeon to enter some of the same prisons he once spent decades in, this time as an advocate and mentor for incarcerated individuals.

Despite his initial nervousness, DeLeon felt that he had the qualifications for the role: being one of the founding members of a globally recognized mentor program at Cheshire Correctional Institution, known as the TRUE Unit, meant building people up. It was no foreign task for DeLeon.

Plus he was working as a canvasser for the Full Citizens Coalition. This new job would allow DeLeon to further grow in this type of work.

Weeks after the job interview, DeLeon learned he didn’t get the job. That hasn’t stopped him, though, from seeking out new opportunities and continuing his work related to criminal justice reform.

DeLeon spends most of his days with an optimistic worldview, keeping a smile on his face and a sense of humor.

When asked if he has any regrets, he acknowledged that he does.

“I think regret is a good thing, because it shows that I am aware of some of the bad decisions I made to put me in the situation I was in,” he said. “Now I can learn from those same decisions.”

At the same time, DeLeon is aware that his ability to do better is in the present moment.

He said he wants people to look at him and say he continued to prove that change was possible even after his release. “In that change, I want to continue to set a path for the people after me,” said DeLeon.