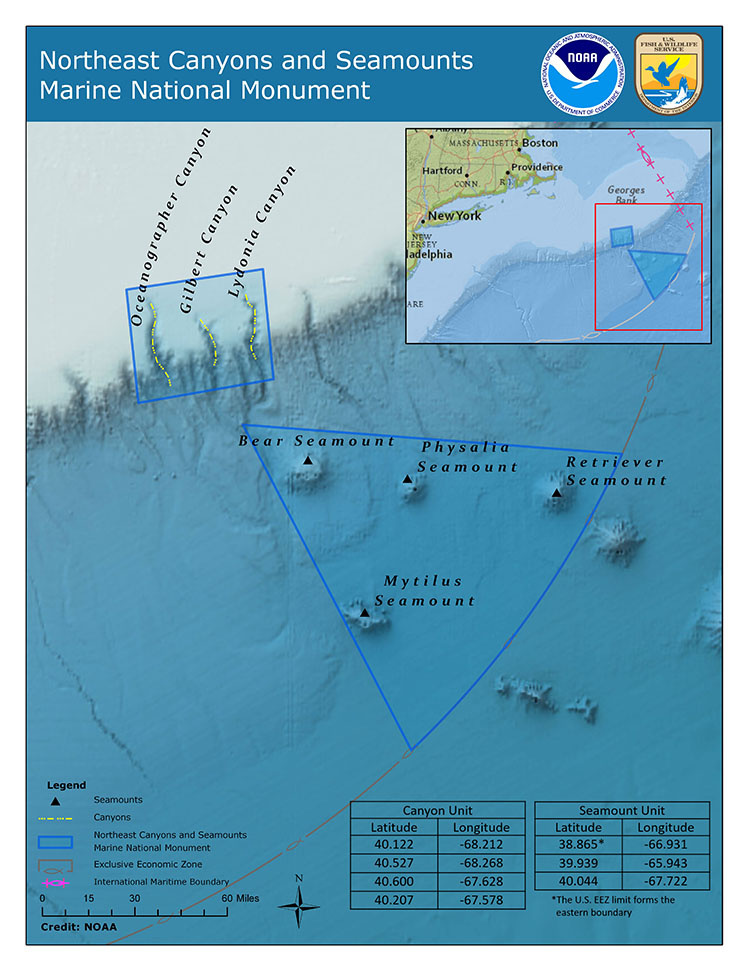

Over the course of my career, I have had the great fortune to bear witness to the grandeur of the 4,901 square miles of the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument off the coast of Cape Cod, a site few have been lucky enough to see from the air to the seafloor.

My first experience visiting this vast wonder was in 1978, when conducting marine mammal surveys. Every single time I went out to the shelf edge, I knew I was entering an unfamiliar world. The color of the water changed. The scent of the air was different. I encountered marine wildlife I had never seen before. In 1984, I first experienced what is now the Monument from the underwater side in a research submersible. It really is like visiting a part of the planet that few have witnessed firsthand before. It’s the twilight zone and the deep ocean. It’s a true marine wilderness.

Each visit after that reinforced the idea that we need to protect these animals and their habitats from long-term harm.

In 2001, my colleagues and I led the first leg of the first expedition for National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) new ocean exploration program. I had the privilege to dive into the deep-sea gorges that run deeper than the Grand Canyon and discover the beauty underneath the surface. It was like something out of a Dr. Suess book. Large and colorful sea creatures like deep-sea corals and fish with strange appendages wandered by the viewports. The beauty and wonder of it all ran from the sky to the seafloor.

The Northeast Canyons and Seamounts were officially designated a marine national monument in 2016, after years of advocacy for the creatures and habitats that reside there. But over the last decade, presidential administrations have played tug-of-war with the monument’s vital protections.

During the first Trump administration, the monument’s protections were rolled back, making the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts vulnerable to disturbances from commercial-scale fishing. During the Biden Administration, these protections were reinstated. Now, in a second Trump administration, we find the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts to be threatened again under the guise of freeing the fishing industry from regulation and increasing seafood market competitiveness.

Opening the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts, or any marine national monument, to commercial-scale fishing has serious consequences for these protected areas, which serve as places of refuge for marine wildlife and the habitats in which they live. Commercial fishing removes and displaces wildlife, impacts biodiversity, and alters ecosystems. We need these protected places to understand the impacts of our activities elsewhere in the sea. But monuments don’t only exist to serve scientists. Most important, the existence of monuments further humanity’s goals of preserving the planet we live on and our collective natural heritage. Monuments serve as a contribution to, and an example for, global conservation efforts.

Much of my career has focused on exploring how ocean ecosystems work, human impacts in the sea, and how we balance human needs and the obligation to protect sensitive and vulnerable places for which we are stewards. The Northeast Canyons and Seamounts are under threat of being harmed in ways from which they may never recover. The area is 1.5% of US waters in the Atlantic region and 0.11% of waters under US jurisdiction in all oceans. Why is this such a problem? Opening this monument to commercial scale fishing will do nothing substantial to improve catch or markets for the industry.

It is more important than ever to stand up for ocean wildlife, ocean places, and our marine monuments and sanctuaries that draw us to the sea. Our future, and our natural heritage, depend on it.

Peter J. Auster, PhD, of Chester is a Research Professor Emeritus of Marine Sciences at the University of Connecticut.