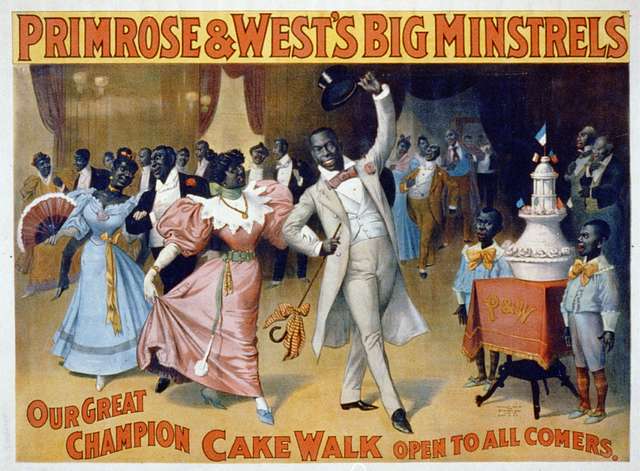

In the 1840’s, across stages in America, minstrelsy was born. During performances, white actors would blacken their faces with burnt cork and wear tattered and unkempt clothing to mock African slaves. Here, tropes like the Mammy, Jezebel, and untrustworthy criminals were constructed for a large audience, creating a false image of the everyday African American.

More than 150 years later, on TikTok, users see a woman depicted as a gorilla. She’s in front of a gas station and has on a pink wig, big fake pink eyelashes, and bright pink nails. While holding a gas station cup, she says with a blaccent, “So my probation officer called. Good news I ain’t gotta do no more community service, bad news it’s ‘cuz there’s a new warrant out for my arrest, teehee.”

Minstrelsy is back, and just like in the mid 19th century, we, the audience consume its contents without a second thought. Seemingly out of nowhere, hundreds of thousands of AI videos depicting Black people being “ghetto” or “ratchet” have flooded our timelines with no end in sight. For me and my peers at Farmington High, as well as other Connecticut schools, it can be hard to avoid.

Minstrel shows were American’s largest form of entertainment. As lower- and working-class whites were the target audience, performances encouraged them to feel superior in a time of financial struggle as the Great Depression left many of them unemployed. Shows were marketed as family-friendly and were often viewed by people of various ages.

The 20th Century saw a shift, as Black actors began to participate in shows as well. They too dressed up in scruffy garb, painted themselves as dark as they could, and portrayed their own people as slovenly and foolish. Minstrelsy opened doors that were previously closed for Black actors and musicians who struggled to make a name for themselves.

They cashed a check using damage to their own community as collateral. This phenomenon can be seen all throughout history; minorities aligning themselves with their oppressors in order to seek special treatment. Only with minstrel shows, this self-deprecating dynamic is broadcasted for everyone to see, having a lasting effect on people’s perception of who Black people really are.

Throughout the 1900s, Broadway minstrel shows died out and Race Films took their place. Due to the public’s newfound reliance on on-screen entertainment, Race films went where minstrel shows couldn’t —reaching the world on a global scale. The pattern of Black creatives pandering to a white audience is evident here, as Race Films succeeded at modernizing tropes of the last generation.

Bleeding into the 21st century, we see this reflected once again with AI. Only now, who receives compensation? Major software and AI database companies only stand to gain from this phenomenon. Programs like OpenAI’s Sora and Google Gemini’s Veo take faces and artwork from across the internet, then generate videos based on prompts imputed by users. It’s free and easily accessible to the public, making it extremely profitable.

This kind of content has made its way onto TikTok, one of the world’s largest social media platforms. With approximately 1 billion users worldwide, TikTok was taken by Sora 2’s launch in late September of this year. Users were bombarded with AI- generated videos, making it difficult to discern what was real from what wasn’t.

The woman in the gorilla video is meant to look absurd. Her excessive appearance followed by a ridiculous yet playful statement, invites viewers to laugh at such absurdity while reinforcing inherent biases. Through slavery, and later minstrelsy, Black women were frequently disparaged in the public eye, often overly masculine and seen as obnoxious or overly sexual. Portraying Black women as gorillas is not a new concept and is a direct reference to the pseudoscience of the 19th century.

Disgraced practices like phrenology, where scientists compare the size and shape of a person’s head to determine their personality traits, morality, and brain capacity, were used to enforce a racial hierarchy: one with white Europeans on top and Black Africans on the bottom. Phrenologists compared skulls of Africans to those of monkeys or gorillas and cited their research as a justification for enslavement.

But AI Minstrelsy doesn’t stop here. It can generate just about anything: A video depicting Black men as deadbeats, in which a Black man throws something at his girlfriend after she asks for child support. Or maybe another about young Black children —feeding the stereotype of Black boys being gangsters and Black girls being overly promiscuous. Anything and everything pertaining to Black people and “the Black experience” can be found here. Once again Minstrel tropes have been modernized for the public, placing an entire group of people in a box they can never seem to escape.

People laugh because they believe their acceptance has no impact on the world around them. Whether you overtly or covertly believe in racist tropes, engaging with minstrel content shows algorithms that this content holds the audience’s attention. It becomes a recurring loop: Someone creates an AI video, algorithms push it out enough to go viral, then someone notices that virality and decides that they want to go viral too. Passive engagement is now easier than ever; people aren’t using AI because they agree with the agenda being pushed, but because it’s an easy and free way to gain popularity and monetary advantage.

At the end of the day, artificial intelligence is only a tool; it can be wielded by many for various purposes. Someone making Minstrel content for free and posting it online with zero pushback is not only alarming but indicative of our political climate. Sora AI may have been the first social media platform to solely implement AI short-form content, but they won’t be the last.

To some, this issue may seem trivial, but when thinking about the broader implications it has on our communities, the danger becomes apparent. Connecticut is home to over 360,000 black Americans, and this content is a reflection of the implicit biases held by our neighbors. A lack of race and class consciousness across our nation invites us to be susceptible to outside agendas. Comedy is used to validate racism, and that racism only stands to divide us from one another and distract us from reality.

Jada King lives in Farmington.