Connecticut lawmakers haven’t adjusted the baseline per-pupil state funding for public education in over a decade. This year, they’ll to consider raising the base rate — and tying it to inflation.

Education Committee co-Chair Rep. Jennifer Leeper, D-Fairfield, said that’s “priority No. 1” for her, potentially resolving a source of growing financial pressure for public schools. On top of that, Leeper said she wants to phase out local school districts’ financial responsibility for students who attend “choice” schools outside of the district, which would give districts still more money to work with.

“My hope is that it will be a House priority bill,” Leeper said.

Leeper said her other priorities include passing a statewide bell-to-bell — all day — cellphone ban and enhancing funding programs to compensate student teachers.

Co-Chair Sen. Douglas McCrory, D-Hartford, did not respond to a request for comment.

Committee Ranking Member Sen. Eric Berthel, R-Watertown, said he hopes to pass legislation that would improve the 2023 Right to Read law, which required schools to adopt curricula aligned with the “science of reading” — methods for teaching reading through five key skills: phonemic awareness, phonics, oral reading fluency, vocabulary and comprehension.

Berthel said he and Leeper worked with advocates to address concerns about the law as it was originally passed. He said Education Committee leaders now recognize that schools need more support from the state to hire specialists who can implement Right to Read curricula effectively and provide tutoring.

“There was a lot of controversy, and a lot of our districts that already had high-performing readers at K-3 said, ‘Why are you forcing me to spend a lot of money to buy this new curriculum?’” Berthel said.

Ranking House member Lezlye Zupkus, R-Prospect, said she’d like to see the General Assembly focus on “mandate relief” — that is, rolling back the “hundreds and hundreds” of legal requirements public schools in Connecticut are subject to. She cited two in particular: a requirement that districts electrify their bus fleets by 2030 and rules requiring trash composting.

“We have kids graduating from high school that cannot read. We have issues in our own public schools. We should be focusing on that,” Zupkus said.

Fixing the foundation

Critics have argued that failing to tie baseline state funding to the inflation rate has cost school districts millions, perhaps billions, of dollars.

Since 2013, the state’s foundation amount for school funding has remained at $11,525. That’s ostensibly how much it costs to educate one student in Connecticut.

From there, the state’s Education Cost Sharing grant formula adjusts this per pupil expenditure based on how many students a district serves from low-income households. It particularly focuses on pupils who are eligible for free or reduced-price meals or who speak English as a second language. It also considers a city or town’s wealth in two ways, looking at the value of its taxable property as well as the income of its residents. Hoping to encourage cooperation and efficiency savings, the state also provides a bonus to towns that send students to regional school districts.

According to the School and State Finance Project, Connecticut’s baseline funding rate of $11,525 wasn’t calculated based on an analysis of “the actual costs associated with educating a general education student.” More pressing, the rate hasn’t been raised since 2013 — even though costs have increased.

If it had been tied to inflation, as tracked by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, that $11,525 in 2013 would be nearly $16,000 today. That’s a potential funding gap of millions of dollars per year in a single lower-wealth district.

Democrats have indicated their readiness to raise the foundation amount this year for the first time in 13 years. In addition, they want to tie the foundation amount to inflation so it continues to rise alongside costs each year. Supporters say doing so would prevent the kind of funding gap that now exists from forming again.

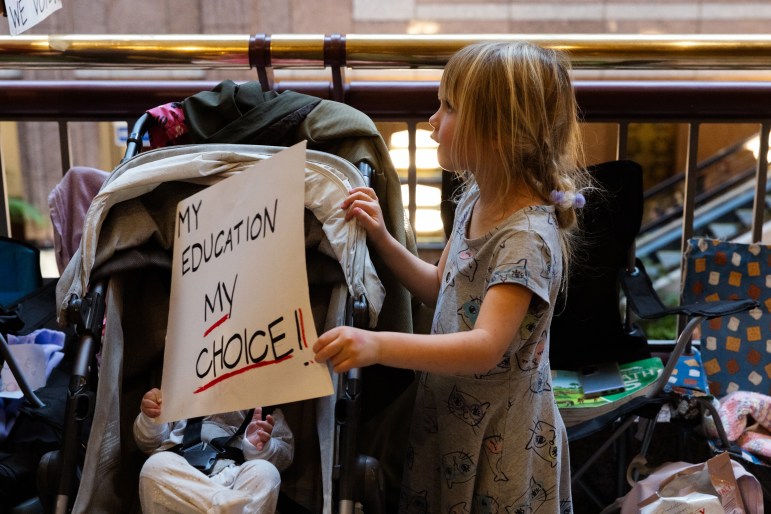

In addition to that, Leeper said she wants to start phasing out the tuition districts pay when a student chooses to enroll elsewhere — in a magnet or charter school, for example. The state cost share would rise in tandem and eventually take over local districts’ portion of costs associated with that student.

Leeper said these funding changes would free up funding and allow districts to direct it toward hiring staff — a common need.

“They could have more reading specialists and interventionists. They could have smaller class sizes because they can hire more teachers. They could have paras [support staff] in more classrooms … more social workers,” Leeper said.

Berthel said tying the ECS formula to inflation might be too much of a challenge for the Appropriations Committee, which he also sits on, to get done this year. “I just don’t know that our budget in the current cycle that we’re in would support that,” Berthel said.

Nor is it clear that tying the foundation amount to inflation would be as effective as it sounds. For example, Berthel said, school costs don’t always align with standard measures of inflation.

“If we bake that into the law and the policy, maybe there’ll be years when the cost-of-living index is really low, but schools have additional exposure because of some other factor that’s not represented in that cost-of-living index,” he said.

As for phasing out the local share when students enroll out-of-district, Berthel said he could “go either way” but expressed some hesitation. “I don’t think we should necessarily be doing that on the backs of every taxpayer in Connecticut,” he said.

The problems with the ECS formula go much deeper than these changes can address, Berthel said. To truly go in and fix it, he said, would require enormous changes at substantial political cost.

“There may be a legislator or two in the building that now would have to go back to their district and say, ‘Hey, I agreed to support fixing the ECS formula, but now it results in, let’s say, 10% less funding for our schools,’” Berthel said.

A ‘bell-to-bell’ ban

Last year, the General Assembly passed a law requiring local boards of education to adopt a policy regulating cellphone use. The policy had to be based on official guidance from the State Board of Education, which recommended removing phones from elementary and middle school classrooms entirely while requiring high school students to keep them off and out of sight.

That stops short of the full statewide bell-to-bell ban Leeper said she’s pushing for this year.

“Even the proximity to your phone means a kid’s thinking about their phone. So, if it’s in your backpack, you’re thinking about it, even though it’s away,” Leeper said. “If it’s actually fully out of sight and away and you know you can’t access it, it frees kids’ brains up from thinking about the phone, and who maybe messaged them, and what they missed.”

Research from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania suggests that teachers have better experiences with stricter cellphone policies in place. Teachers in New York have also reported classroom improvements since the state implemented its own bell-to-bell ban last year, according to an article from Spectrum News.

The Connecticut Education Association and AFT Connecticut, the state’s two major teachers’ unions, both support a bell-to-bell ban.

Leeper, who served on the Fairfield Board of Education before being elected to the General Assembly, said it can be challenging for school boards to implement policies if parents are opposed. Making the policy statewide could take some of that pressure off, she said.

However, the Connecticut Association of Boards of Education president Meg Scata said she thinks a statewide ban is unnecessary. She said districts are addressing the problem locally already, and some students — for example, multilingual learners or those receiving special education — need their phones for instructional purposes.

Passing a statewide bell-to-bell ban now, she said, would be like “closing the barn door after the horses are out.”

Both ranking members expressed views similar to Scata’s.

“Banning, another mandate. I’m for schools having a policy, but let them have their own policy,” Zupkus said.

Berthel shared an example he heard from a parent of a child with Type 1 diabetes. The child’s phone is connected to a device that monitors blood sugar and can alert the parents if the child has a crisis. That might not work if the phone is shut off or not accessible.

Student teacher pay

Many Connecticut districts need teachers, but becoming a teacher can be expensive.

At a summit at the Capitol last month, Hannah Spinner, a graduate student studying education at the University of Connecticut called the costs of teacher training “astronomical.”

“The return on investment that many people who want to become teachers see in the education profession is just not worth it to them,” Spinner said. “When you can accrue $100,000 in loans to get your degree to be able to teach, and then your starting salary is half that, that’s a problem.”

Spinner said she has friends who went into business and engineering because those tracks offered paid internships, while public education does not.

To help address the issue, Leeper said she’d like to enhance Connecticut’s support for student teachers. That could include expanding existing initiatives like the Aspiring Educators Scholarship, which gives up to $10,000 to students from certain Connecticut districts, or NextGen Educators, in which participating districts hire student teachers at a substitute pay rate.

Berthel expressed reservations about putting taxpayer dollars toward funding student teaching positions, which he noted are “part of their curriculum.”

“If we have someone that’s in school to become an accountant, and they go and take an internship to do an accounting job, do we pay them to do that? No,” Berthel said. He said that lawmakers can help make Connecticut affordable by cutting taxes and removing the public benefits charge from electric bills.

Will lawmakers take up special education, homeschooling?

Leeper said she’s looking forward to reviewing reports from a special committee, established last year, known as the Building Educational Responsibility with Greater Improvement Networks (BERGIN) Commission. The group was tasked with reviewing the state’s special education needs and providing suggestions. It’s not clear whether that will translate into a bill during this year’s session, however.

Homeschooling has also received heightened attention following two high-profile cases last year. One involved a Waterbury man allegedly held captive for 20 years after being withdrawn from public school. The other involved an 11-year-old girl who died of starvation after her mother announced plans to begin homeschooling.

The cases, along with a report from the Office of the Child Advocate— which concluded lax regulations have meant some children aren’t getting a proper education, and the system has been used to cover up abuse — prompted questions about whether the state does enough to oversee homeschooling.

Leeper said if the committee does take up a bill, “it will really be focused on accountability for kids to have access to their state constitutional right to a public education or equivalent.”

Although both Zupkus and Berthel said the aforementioned cases were horrifying, neither considered new homeschooling regulations an effective response.

“No piece of legislation would have stopped [those cases] from happening. If there was, I think we would all be on board to put something in place,” Zupkus said.

Echoing what some homeschool advocates have argued, Berthel said the main failure lies with the Department of Children and Families. “I think maybe we need to fix some of our own internal mechanisms first before we start putting these directives on these families,” Berthel said.

Ultimately, Berthel praised the work of the Education Committee and the members from both parties who sit on it.

“The Education Committee is the most important committee in the building,” he said. “From the kindergartner that started back in September, or the high school senior who’s going to graduate in four or five months, no one else is responsible for ensuring that they get the best that they can from our public schools.

“It’s a pretty high bar, and it’s a pretty high honor to be in that role with a lot of other legislators on that committee,” Berthel said.

The Education Committee meets for the first time this session at 9:30 a.m. Wednesday.