|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Expanding natural gas infrastructure is a centerpiece of President Donald Trump’s agenda to lower energy costs and boost the fossil fuel industry. He has referred to Democrats opposed to such projects as “anti-energy zealots.”

But political support for gas pipelines has run into powerful local opposition in a relatively conservative community in Connecticut, where residents are leading a campaign to block a $272 million buildout of the Iroquois Gas Transmission System.

The epicenter of the debate is Brookfield, on the far edge of suburban Fairfield County, where Iroquois’ owners are seeking approval to add two new compressors to an existing station in order to push an additional 125 million cubic feet of gas through the pipeline each day, without having to lay new pipes. The project has received tentative support from the administration of Gov. Ned Lamont, a Democrat, and is awaiting final approval on air quality permits from the state.

But beyond typical opposition from climate-focused organizations such as the Sierra Club and the League of Conservation Voters, the Iroquois project has also faced pushback from a bipartisan group of local officials, including members of the town’s Board of Selectmen and the town’s all-Republican statehouse delegation.

During a public meeting on the project — which company representatives attended — in January, state Senate Minority Leader Stephen Harding, who represents Brookfield, said he lives just a few miles away from the compressor station. Harding echoed the concerns of many of his constituents regarding the compressor station’s proximity to nearby homes and a middle school.

“These are health risks for our kids, for our families, these are environmental risks for everyone in our community,” Harding said. “This is being put up literally yards away from a school, a middle school, which my children are going to be attending. This needs a full, transparent process where every single one of my constituents, every single one of my neighbors have an ability to object to this.”

And Harding made his own position clear. “This should not be approved in any circumstance,” he said.

Similar sentiments can be seen in signs protesting the expansion that dot lawns around Brookfield, a mixture of rural and suburban neighborhoods adjacent to Candlewood Lake. The town narrowly voted for Trump in 2024 and has backed the Republican candidate in four of the last five presidential elections. Now, the town’s opposition to Iroquois’ plans have put local Republicans at odds with a key part of the national party’s energy agenda.

The Iroquois project predates the current Trump administration and its efforts to ease the path for new gas infrastructure. But Connecticut Republicans — along with some Democrats — have for a long time blamed the lack of ample gas supply for the region’s high energy costs. Because New England is positioned at the tail end of the national pipeline network, its residents pay a premium for the gas needed to heat their homes and produce electricity.

The latest backlash in Brookfield follows a similar pattern of strong local resistance to energy infrastructure upgrades throughout Connecticut. Community opposition has delayed, threatened or led to the cancellation of projects to build new transmission lines, solar arrays, windmills, and battery storage facilities.

While political leaders on both sides of the aisle often tout the benefits of energy expansion, their support tends to fade when local considerations come into play.

“The opposition to this runs across all party lines — unaffiliated, Democrat, Republican — and there are some good reasons for that,” said Brookfield First Selectman Steve Dunn, a Democrat.

The reasons in this case, Dunn said, include the emissions released by the new compressors — which would be powered by burning gas from the pipeline — as well the noise and vibrations produced by the facility. Many residents also fear the risk of a catastrophic explosion that could damage nearby homes and endanger students at the Whisconier Middle School.

“Our residents are only concerned with our town, our children in the school 1,800 feet away, and the safety of this particular facility,” he said.

State Rep. Martin Foncello, R-Brookfield, said the opposition to Iroquois’ compressor station dates back more than two decades to when he served as the town’s first selectman. In 2002, the Connecticut Siting Council approved the construction of the existing two compressors in Brookfield over local objections. At the time, in the aftermath of 9/11, residents were focused on the safety of the facility, Foncello said.

“There were concerns that, you know, terrorists or other individuals were going to blow up the pipeline,” he said. “Fortunately, nothing like that happened.”

Last month, Foncello submitted testimony to DEEP urging the agency to deny Iroquois its remaining permits. He cited safety concerns, as well air pollution and other quality-of-life issues.

Samantha Dynowski, the president of the state chapter of the Sierra Club and a steadfast opponent of adding new sources of gas, said she welcomed the support of Republicans in Brookfield and hoped the experience would lead them to shift their stance on other natural gas projects beyond their own communities.

“The negative impacts you’re going to have in Brookfield — the air pollution impacts, the climate impacts, the health impacts — should be a concern across all fossil fuel expansions,” she said. “It should be eye opening.”

Who benefits?

Both Harding and Foncello said they believe Connecticut needs more natural gas to fuel power plants and meet increasing customer demand. Last year, Harding and other Senate Republicans introduced legislation to address high electricity prices, which included a provision requiring the state to “study methods by which the supply of natural gas may be increased in the state.” The bill was not successful.

In separate interviews this month, both lawmakers defended their stance opposing the Iroquois project by pointing out that the pipeline’s owners plan to use the new capacity to sell more gas to utilities in New York, where the pipeline terminates after crossing under Long Island Sound.

“Connecticut is getting no benefit, we’re not getting any increase in supply from this expansion” Harding said. “It’s expanding it strictly to provide more natural gas to New York.”

But Iroquois leaders and other experts said the reality of the situation is more complicated. In addition to serving customers in New York, Iroquois currently delivers about 30% of its gas to customers and power plants in Connecticut, according to company records. The proposed capacity expansion would boost the pipeline’s overall capacity by around 8%.

Ira Joseph, a senior research associate at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, said that increasing the Iroquois pipeline’s capacity should lower the price of the gas that moves through it relative to the U.S. benchmark, regardless of its final destination.

“It’s certainly targeted for the Long Island or New York market,” Joseph said. “But I don’t think that in any way prevents potential new customers in Connecticut from emerging if they wanted to make those type of investments. That definitely is possible.”

In an emailed statement, Iroquois spokeswoman Ruth Parkins said the project will help ease pipeline constraints in both New York and New England during the winter, when the demand for gas is at its peak.

“The ExC [Enhancement by Compression] Project will enhance the reliability and availability of natural gas supplies for Connecticut’s natural gas consumers and power generation fleet since additional quantities of natural gas will be flowing into and through the state, and available for consumption within the state on a majority of the days throughout the year,” she said.

In addition, Parkins noted that Connecticut relies on pipelines passing through other states — including New York — to supply all its own natural gas.

“If it weren’t for neighboring states not taking a narrow-minded view on infrastructure to get the gas to Connecticut, everyone would be on oil,” Parkins said.

Other critics have questioned the need for any increase in Iroquois’ capacity, given the pledges from both New York and Connecticut to lower their overall greenhouse gas emissions over the next several decades.

In New York, those efforts include a state law that would ban the use of gas heating systems and appliances in most new buildings. That law was supposed to take effect on Jan. 1, before Gov. Kathy Hochul paused implementation for at least another year.

Tai Michaels, an activist with the Sunrise Project New York, spoke out against the project at a virtual public forum earlier this month. “We have stated strong climate goals here in New York City, which make this project not only inadvisable economically, and inadvisable from health perspective, but [it] just plain doesn’t make sense,” Michaels said.

Locally, however, opponents of the new compressor station have largely framed their case around the local impacts of the project within Brookfield — rather than the larger debate around climate change and greenhouse gas emissions.

“I think we’ve conscientiously said, from the standpoint of this project, if you make it about carbon, you run the risk it has some sort of political problems,” said Daniel Myers, an organizer with a group of residents fighting the project.

“Locally, the calculus is they’re polluting our town because it’s more profitable for them…. We’re not getting any reduction in our energy costs,” he added. “In that lens, it doesn’t matter whether you’re ‘Drill, baby, drill,’ or you’re chaining yourself to a tree. It’s not a good deal for you as a Brookfielder, right now.”

Seeking changes

Like much of Connecticut, Brookfield already experiences poor air quality and particulate-matter pollution that blows into the state from the west. It’s located in Fairfield County, which the U.S Environmental Protection Agency has designated in “severe nonattainment” with air quality standards.

For that reason, many local opponents argue that if compressor stations are going to be expanded, the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection should force Iroquois to utilize less-polluting technologies such as all-electric motors.

“It’s not a huge expense considering you’re protecting the environment, you’re protecting Connecticut and Brookfield residents from all this particulate matter,” said Dunn, the town’s first selectman. “It seems to me a no-brainer, right?”

Other ideas floated by town officials and residents include adding security guards around the compression station and conducting continuous monitoring of its emissions, particularly in the vicinity of the middle school. Some criticism has focused on the process by which the company and DEEP have engaged with the public.

In January, the town, along with the environmental group Save the Sound, filed a lawsuit alleging that DEEP failed to provide opponents to the project with adequate opportunities to raise concerns before the agency reached a final decision on the project. That lawsuit remains pending.

Harding, the Senate Republican leader, also criticized Iroquois’ owners for not responding to input from Brookfield residents.

“The company has not been transparent, has not really listened to the public at all,” he said. “The public has given them options to make this a much safer, healthier project for the community, and they’ve shut all them down.”

Iroquois declined to respond directly to criticism that the company hasn’t done enough to assuage local concerns.

During last month’s public meeting, however, Michael Kinik, Iroquois’ director of operations and maintenance, said the company had responded to feedback by agreeing to install devices on both the new and existing compressor turbines to lower noise and reduce emissions.

“This project has been reviewed for more than five years by multiple state and federal agencies,” Kinik said. “Along the way, Iroquois has revised designs, performed additional modeling, added emissions controls, and accepted permit limits that are more stringent than what the regulations require.”

DEEP’s public analysis of the project states that Iroquois examined whether to use electric compressors to power its expansion. That idea was ultimately rejected, the company said, due to the need to upgrade electrical connections that could take up three years to complete and add between $45 million and $50 million to the project’s cost.

Will Healey, a spokesman for DEEP, said in a statement that the agency is only required to consider the project’s impact on air pollution as part of its evaluation, and not who the intended customer of the gas is.

“DEEP required Iroquois to investigate the economic and technical feasibility of using electric turbines in accordance with applicable permitting law and determined that, due to the cost and technical challenges, electric turbines would not be required for this project,” Healey said. “This does not preclude Iroquois from volunteering to do so if they chose. However, to date Iroquois has not expressed a desire to use electric turbines.”

As part of its analysis of the project, DEEP also determined the addition of the two new compressors would not meet the threshold for a major modification — which is subject to more stringent review — because the increase in ozone-forming pollutants would not exceed 25 tons per year. Critics of the project, including Myers and Save the Sound, questioned the agency’s methodology for reaching that conclusion.

As for concerns that the compressor station could explode or experience a gas leak, Joseph, the Columbia University researcher, said that while such incidents are rare, they are a risk for older pipelines. The Iroquois pipeline began operating in 1992.

“You’re trying to create a bigger system on a piece of infrastructure that’s not new,” Joseph said. “There’s risks that always come with that.”

New York’s role

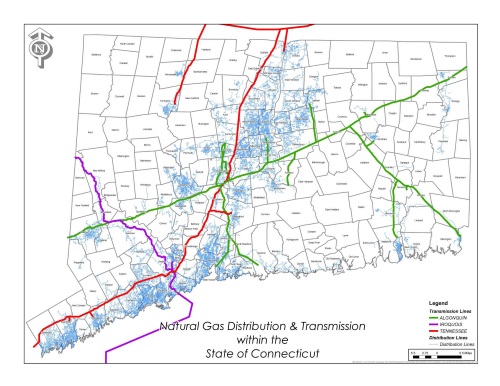

The Iroquois pipeline is one of three major gas transmission pipelines serving Connecticut. The other two are the Algonquin and Tennessee systems, both of which enter the state from New York and follow a northeasterly route to service the rest of New England. Parts of the Tennessee pipeline also enter the state from Massachusetts.

The Iroquois and Algonquin pipelines intersect in Brookfield, near the site of the existing compressor station and the proposed expansion.

Each of those pipelines already operate at or near capacity, creating a supply bottleneck during winter months when gas is used to both heat homes and fuel the power plants that produce the bulk of the region’s electricity.

Lamont has publicly expressed interest in expanding the capacity of one or more pipelines running through New York into Connecticut, often drawing criticism from environmental groups who want to wean the state off of natural gas. While the governor has yet to publicly weigh in on the Iroquois project, DEEP issued draft permits for the new compressor stations last summer. A final decision is not expected until March, and could be pushed back due to pending litigation.

Efforts to expand pipelines running through New York are also often met with strong local opposition.

In November, the New York Department of Environmental Conservation blocked approvals for the proposed Constitution Pipeline project that would serve as a major artery for gas flowing to New England by linking up with the Iroquois and Tennessee systems. At the same time, the NYDEC approved another pipeline intended to serve New York City and Long Island. Regulators have also granted permits necessary for Iroquois to build new compressors in upstate New York.

Lamont has said that he’s in discussion with Hochul and federal officials regarding plans to build out pipeline capacity for the region. Last year, the governor traveled to Washington, D.C. to meet with Energy Secretary Chris Wright and Interior Secretary Doug Burgum regarding energy issues, including the demand for natural gas.

“It’s not easy because of 2040 zero-carbon goals,” Lamont told reporters following his return from that trip. “But, you know, [Hochul’s] got some energy needs of her own. Let’s say the discussions have to continue.”

Rob Blanchard, a spokesperson for the governor, said those discussions have not included an agreement to approve pipeline projects serving Connecticut in exchange for allowing Iroquois’ compression project to move forward.

During a press conference last week regarding his own energy plan, Republican gubernatorial candidate Sen. Ryan Fazio, R-Greenwich, said the decisions by New York regulators amounted to a violation of interstate commerce. Fazio encouraged Connecticut to take legal action against its neighbors. (Fazio serves as the ranking member of the legislature’s Energy and Technology Committee.)

“New York is clearly embracing the fact that they’ll need more natural gas for their own residents and their own state economy,” Fazio said. “They’re doing what’s necessary to accomplish that while essentially — how should I say — rejecting the concerns of New England residents. So that gives Connecticut more leverage in any discussion on several different affairs, including Iroquois.”

Fazio said he that while he would like to see DEEP address some of the local concerns that have arisen around the Brookfield compressor station, he is not opposed to the project. His district is also home to the Tennessee pipeline, which enters the state in Greenwich.

“I’m open to anything,” Fazio said. “Again, I don’t view [more gas] as a nice-to-have. I view this as a necessity for the New England and for the Connecticut economy.”

Harding declined to say whether he would support the Iroquois project in Brookfield if it were a part of a larger regional effort to boost the supply of natural gas in Connecticut.

“We’re talking about hypotheticals that currently don’t exist,” Harding said. “I’m talking about this project right here before us right now. So, this is the deal we have at this moment.”

“I think any senator from any party, from anywhere, would tell you that if you have more gas supply that could benefit affordability with electric rates, great,” Harding added. “But if it’s going to involve the public, you have to have their input, be transparent with them and work with them. And they’re just not doing that here.”