A disease that may cost the United States as much as $362 billion a year in medical expenses and lost productivity receives about $13 million in annual research funding from the National Institutes of Health. I am one of the millions of Americans living in that gap.

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME/CFS, is a complex disease that attacks multiple systems in the body. Because of the overlap with Long Covid —studies estimate that about half of Long COVID patients meet the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS— researchers now believe as many as 9 million Americans may now be living with it. Roughly a quarter are housebound or bedbound.

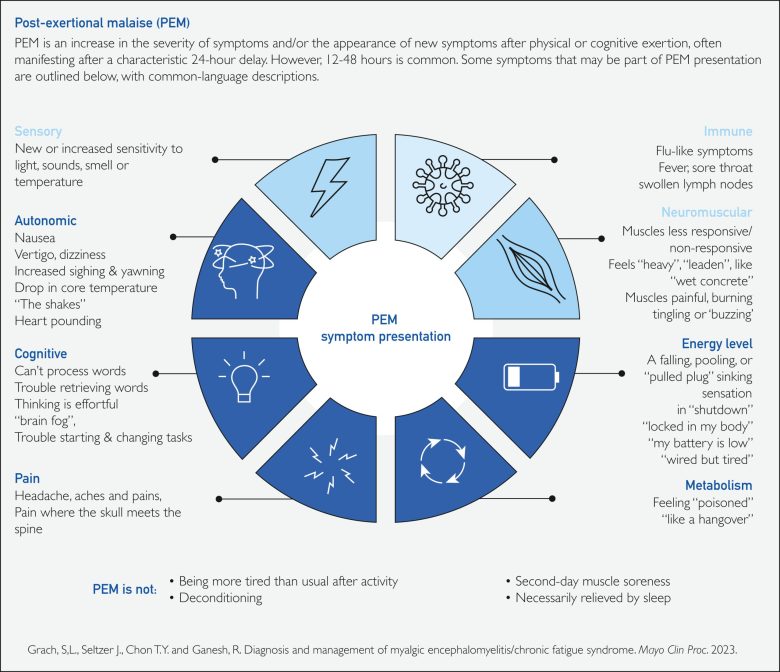

For patients, daily life is ruled by a cruel equation: spend too much energy, pay later. A shower, a phone call, or walking to the mailbox can trigger what’s known as a “crash” —a delayed collapse of symptoms that can last for days, weeks, or months. In those stretches, people can become unable to sit upright, tolerate light or sound, or even speak more than a few words at a time. There is no diagnostic test, no FDA-approved treatment, and far too few clinicians who know how to recognize or manage the disease.

The economic consequences are enormous. Many people with ME/CFS can no longer work at all; others can work only a few hours a week. Researchers estimate that lost productivity alone costs the U.S. tens of billions of dollars each year, on top of billions more in medical spending. For individuals, the average combined hit from lost income and out-of-pocket costs has been estimated at $20,000 to $23,000 per year. Families often lose a second income when a spouse or parent becomes a full-time caregiver.

Yet federal research funding bears almost no relationship to that burden. NIH spends roughly $13 million a year on ME/CFS —far less than it devotes to other serious chronic illnesses with comparable or lower estimated costs, such as HIV/AIDS and breast cancer. Experts have suggested that ME/CFS funding would need to rise roughly fortyfold to match the disease’s impact.

In 2024, NIH approved the first-ever ME/CFS Research Roadmap, a plan developed with scientists, clinicians, and people living with the disease. It lays out a clear sequence: first, give doctors reliable tools to diagnose ME/CFS early and consistently, especially its hallmark delayed crash after exertion. Second, build the core infrastructure modern research depends on —a national patient registry, shared biobanks, and a data hub so researchers can compare results and identify subgroups. Third, create a trial network built around the realities of this disease, with home-based or low-burden participation and the ability to test promising therapies in small, careful studies and then quickly scale up what works.

This isn’t an open-ended wish list. It’s a practical blueprint for unlocking treatments in a disease that has been ignored for decades, and for building tools that can also serve Long COVID and other infection-related conditions. But a roadmap without fuel goes nowhere. The plan does not yet have dedicated funding, specific timelines, or clear benchmarks for success.

Congress has started to stir. A recent Senate spending report recognized the urgency of ME/CFS, praised NIH for approving the roadmap, and asked the agency to explain how it will carry it out. That is better than silence. But patients have learned that report language and memos do not, by themselves, build registries, run trials, or bring new therapies into clinics.

I know the cost of delay in my own life. Ten years ago, I was an active professional, building a career and a future. ME/CFS stripped away my job, my independence, and many of the small rituals that make a life feel like it’s mine. At my worst, I would lay in a dark room unable to speak or move, saving up what little energy I had for four days just so I could whisper “help.”

Even now, talking too long on the phone, brushing my hair, or transferring to a wheelchair can trigger a crash that sets me back for days or weeks. My family has become my care team. My friends have become advocates. Their dedication keeps me afloat, but it cannot substitute for a functioning research system.

Congress can change this. Lawmakers should direct NIH to dedicate a multi-year funding stream to the ME/CFS Roadmap, require clear milestones and annual progress reports, and ensure that the new research infrastructure also serves Long Covid and related conditions.

This is not only a moral question. It is a fiscal one. Every year that ME/CFS remains under- researched, more people fall out of the workforce, more families burn through savings, and more costs quietly accrue to disability programs and health systems. For a fraction of what the disease already costs the country, we could build the scientific foundation needed to prevent some of that loss.

Millions of Americans are waiting. I am one of them. We do not need another decade of hearings or essays documenting neglect. We need Congress to give NIH a funded, accountable mandate to follow the map it has already drawn—and to judge success by whether fewer people are forced out of work and out of their lives.

NIH has the roadmap. It’s up to Congress to decide whether it leads anywhere.

Elizabeth Ansell of Greenwich is the founder and executive director of #NotJustFatigue, an organization advocating for people living with ME/CFS.