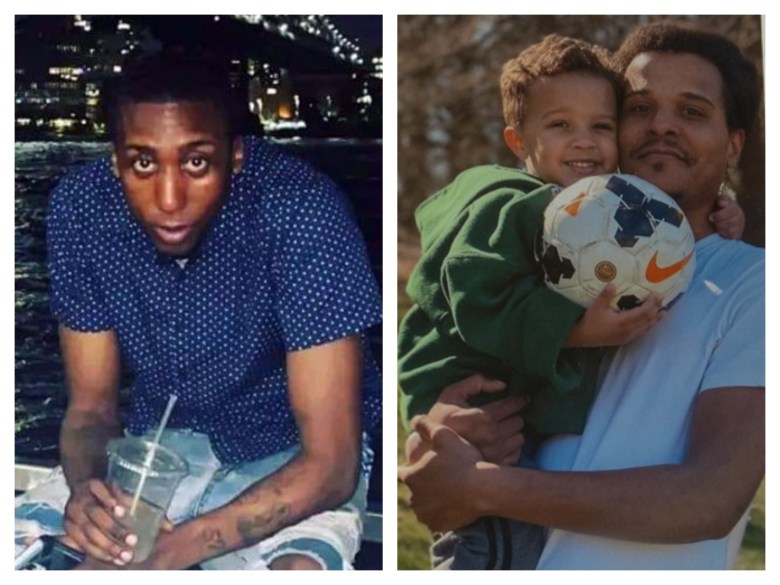

An investigation by the Connecticut Office of the Inspector General released Monday found that “significant medical errors” were made when prescribing methadone to Ronald Johnson and Tyler Cole, two young men who died from the combined effects of methadone and other prescribed medications while incarcerated at Garner Correctional Institution.

“The investigation suggests that both Johnson and Cole received initial doses of methadone that were too high for them, and their doses were increased too rapidly,” the report read. “The investigation further suggests that insufficient attention was given to the fact that Johnson and Cole were receiving medications that enhanced the respiratory suppression effects of methadone.”

The state Department of Correction has administered a program known as medication assisted treatment, or MAT, since 2013, for patients addicted to opioids or heroin. As of last year some type of MAT existed in 10 of Connecticut’s 13 correctional facilities. The department contracts with Recovery Network of Programs Inc. in Shelton, which is responsible for distributing methadone at Garner.

Johnson had been transferred from Rikers Island to Garner in July 2024. When he was first admitted to Garner, he was found to have “moderate to severe” opioid use as well as a history of other drug use, according to the inspector’s report. On July 10, 2024 he tested negative for opioids and was prescribed 30 mg of methadone, which was increased to 40 mg after two days.

According to the report, Johnson was found with an inmate request form in his pocket. On the form, he had written, “I think I could be having a bad reaction to the methadone because my feet are very swollen till the point that it is noticible.” He had also spoken with a friend the day before his death in which he’d spoken about his swollen feet.

According to the report, a white pill was found near Johnson that DOC investigators identified as Vraylar, an antipsychotic used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The state Medical Examiner’s office later contended that the drug was Prozac. Johnson hadn’t been prescribed either medication.

Guidelines from medical organizations, cited in the report, warn that doctors should take caution not to increase doses of methadone too quickly and to prescribe lower doses to patients who are considered to be “high risk.”

While an initial methadone dose can be between 10 mg and 30 mg, The College of Physicians & Surgeons of Manitoba advises that for “high risk” patients, that first dose should be between 5 mg and 20 mg. High risk patients include people who are on sedative medications or antipsychotics, as well as those who have not taken opioids for a significant period of time.

At the time of his death, Johnson had been incarcerated for nearly two months, meaning it was likely he had not taken an opioid for a significant period, and he was being prescribed an antipsychotic. The Inspector General’s office said that these facts should have prevented the medical staff from starting him at such a high dose of methadone or increasing that dose so quickly.

“In Johnson’s case, it is likely that his body could not handle the amount of methadone that he was receiving each day, and it accumulated to a toxic level that (along with the Seroquel and Zyprexa) caused him to stop breathing,” the report read. “His death should have raised immediate red flags in DOC regarding whether other inmates were receiving medically appropriate doses of methadone.”

Just two days after Johnson’s death, another young man at Garner, Tyler Cole, died from a combination of methadone and antipsychotic drugs he was prescribed.

During his intake at Bridgeport Correctional Center on June 13, 2024, Cole told medical staff that he had used heroin and drank Hennessy cognac that day. Soon after, he was transferred to Garner. It was more than a month later, on July 19, when Cole was first given methadone. He was given an initial dose of 30 mg. The next day, it was raised to 40 mg.

Like Johnson, Cole would have been considered a high risk patient, since he had not taken an opioid for over a month and was being prescribed both a sedative and an antipsychotic medication.

The same guidelines from the College of Physicians & Surgeons of Manitoba say that methadone doses should be increased by 5 mg every 3 to 5 days, or 10 mg every 7 days. The American Society of Addiction Medicine advises increasing methadone doses “no more than 10 mg approximately every 5 days.”

[RELATED: Drug overdoses in CT prisons raising alarms]

A lawyer for Cole’s family, Ken Krayeske, filed a claim with the state’s Claim Commissioner in 2025 asking for permission to sue the Department of Correction and requesting $25 million in damages. Krayeske called the increase from 30 mg to 40 mg within 24 hours a “pretty outrageous” jump, which wouldn’t have given Cole time to build up tolerance to the drug.

“Certainly, his dose should not have been increased to 40 mg after only one day in the program,” the Inspector General’s report read. “It is likely that methadone was starting to accumulate in his system; but the methadone’s interaction with the antipsychotic drugs and the Clonazepam (a benzodiazepine) depressed his respiration to the point where he could not breathe.”

The Inspector General’s report did not find that medical professionals who prescribed the methadone engaged in any “criminal action.”

“Johnson and Cole should have been prescribed no more than 20 mg of methadone per day for the first three days of therapy. Perhaps, even a lower dose was more appropriate. Thereafter, the dose should have increased at the rate of no more than 5 mg every 3 to 5 days with careful assessment of their reaction. Instead, they received the typical initial dose of 30 mg that ramped up quickly to 40 mg with fatal consequences,” the report read.

The report also notes that, in both cases, doctors or medical professionals who prescribed the methadone did not meet in person with either of the men.

Reached by phone, Cole’s mother, Tracy Ciccone and his stepfather Jason Ciccone said they wanted the Department of Correction and the medical professionals involved with Cole’s death to be held responsible.

“ This can’t happen again to other people,” said Jason Ciccone. “It’s a tragedy, and going forward they’ve really got to clean things up.”

Tracy Ciccone said she felt the people involved should lose their jobs, and that Cole’s son should receive some type of monetary compensation for the events of his father’s death.

“It’s frustrating, I think, for us, because there’s a little boy whose dad was killed. There’s a mom who lost her son, and the Office of the Inspector General says ‘This is tragic, but I can’t take any action against anybody,’” said Krayeske.

The Inspector General’s report warned against eliminating methadone programs in prisons overall, noting that allowing incarcerated men and women who are detoxing from opioids to access methadone improves their ability to reenter their communities after they leave prison. But the report said the department should take “immediate and substantial steps” to address how the methadone program was being run.

Andrius Banevicius, spokesperson for the Department of Correction, said in a statement to the Connecticut Mirror that after Cole and Johnson’s deaths, the department conducted a review of the Medication Assisted Treatment program “to ensure that it is being administered as effectively and safely as possible.”

According to the report, and to Banevicius, the Department of Correction plans to hire an addiction medicine specialist to work across the prison facilities, and they will no longer start patients at Garner Correctional Institution on methadone because of the risk of combining methadone with antipsychotic medications.