On August 25, the Hartford area broke a 37-year-old record for the most days in a year with temperatures at or above 90 degrees. Two days later, Hurricane Laura was the first Category 4 hurricane to make landfall in southwestern Louisiana since recordkeeping started. Meanwhile, massive wildfires continue to rage across the western United States.

It is abundantly clear that climate change is not a future event; it is happening now, and it affects our lives, and our health.

These are the conclusions in a report released this month by the Center on Climate Change and Health at the Yale School of Public Health.

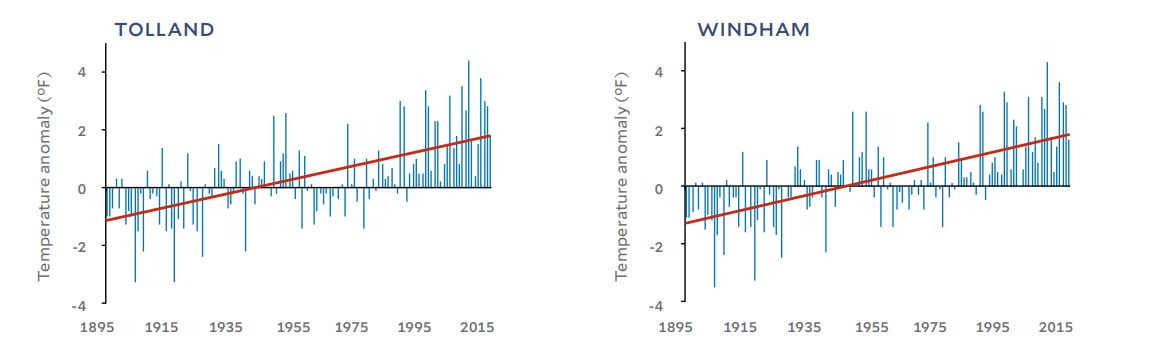

In Climate Change and Health in Connecticut: 2020 Report, we tracked 19 indicators on climate change and health in Connecticut across four broad categories — temperature, extreme events, infectious diseases, and air quality — and found disturbing trends in each.

Our findings included:

- During 2010-2019, there were nine federal disaster declarations for weather-related events in Connecticut, compared with only 13 in the previous 56 years. Climate change is making coastal storms more intense and extreme precipitation events, as well as coastal and inland flooding, more frequent. Hurricanes and other weather disasters directly cause deaths and injuries and also damage infrastructure, like electricity, water treatment, and transportation, that is critical for public health.

- Seven of Connecticut’s 16 Superfund sites are vulnerable to the effects of climate change. In Connecticut, these sites range from old industrial sites to waste lagoons, quarries and landfills. More intense hurricanes and larger rainfall events may damage Superfund sites and potentially release toxic contaminants into ground or surface water, the air, or the soil.

- During 2001-2019, of 28 mosquito species found in Connecticut to carry viruses that cause human disease, 10 showed trends of increasing abundance, whereas only three showed trends of decreasing abundance. Mosquito abundance is a key factor that influences the capacity of a mosquito to transmit a virus and the rate at which infections spread.

While climate change affects everyone, it does not affect everyone equally. Climate change is known as a “risk amplifier,” meaning that many existing risks to health — whether environmental, economic, demographic, social, or genetic factors— are intensified by climate change impacts. Populations disproportionately vulnerable to the effects of climate change include those with low income, communities of color, immigrant groups (including those with limited English proficiency), indigenous people, children and pregnant women, older adults, vulnerable occupational groups, people with disabilities, and people with preexisting or chronic medical conditions.

The report’s results are a call to action to enact changes that will protect human health, now and in the future.

First and foremost, swift action is needed to mitigate climate change by sharply reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Commendably, Connecticut has committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions below 2001 levels by 45% by 2030 and 80% by 2050. However, to avoid catastrophic climate change impacts, this commitment needs to be strengthened to 100% by 2050 at the latest.

Such steep reductions require strong energy conservation and efficiency measures, rapid deployment of zero-carbon electricity by replacing electricity generated by fossil fuels with electricity generated by solar and wind, and electrification of the transportation and building sectors. Importantly, because burning fossil fuels also results in the ozone and particulate matter pollution responsible for roughly 100,000 deaths per year in the United States, these actions provide life-saving health benefits in the near-term.

Second, Connecticut must expand its work to prepare for and adapt to the climate change impacts that are already occurring and will worsen in the future.

This requires more than physical infrastructure changes, like seawalls or utility upgrades. The state also needs to invest in our public health infrastructure and community support systems in order to track climate-sensitive health outcomes (like heat-related illness and emerging insect-borne diseases), provide timely and actionable alerts to the public, and implement preparedness activities. Further, policy changes are required to assure that populations most vulnerable to the effects of climate change are protected in both the near and long-terms. For instance, policies to make housing more affordable, healthy, and energy efficient also make those homes more climate resilient. In keeping with the concept of procedural equity, such policies must be developed through meaningful collaboration with vulnerable populations to assure that the policies meet community needs.

This is a consequential moment. This fall, the Connecticut Governor’s Council on Climate Change is considering a suite of greenhouse gas reduction strategies and climate adaptation actions. We urge Gov. Ned Lamont to ensure that the final recommendations that reach his desk are effective, equitable, and ultimately, implemented.

Globally, nations are setting out COVID-19 economic recovery plans. A new report from the International Energy Agency identifies a sustainable recovery pathway focused on actions like renewable energy development and energy efficiency retrofits for buildings, which deliver triple benefits of the creation of new, good jobs; economic activity; and —critically— greenhouse gas reductions in line with scientific targets that stave off climate catastrophe. The window is closing on these targets being achievable.

The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now. Like planting a tree, the best time to tackle climate change was years ago. The second best time is now. To protect public health, let’s get going.

Laura Bozzi, Ph.D., is director of programs at the Yale Center on Climate Change and Health and lead author of the climate change report. Robert Dubrow, M.D., Ph.D., is a professor at the Yale School of Public Health, faculty director of the Yale Center on Climate Change and Health, and co-author of the report.