Healthcare in the United States is in crisis and requires immediate action. Compared to other wealthy countries, we are an extreme outlier in terms of costs, outcomes, and service quality.

We spend more than double the amount on healthcare than other countries, five times more on administrative costs alone, and healthcare spending represents 18% of our Gross Domestic Product (GDP), versus 10-12% in other wealthy nations.

We live in a country where millions are uninsured, and many more are underinsured. Compared to other wealthy countries, we have the highest rate of preventable deaths, and our life expectancy is lower by more than four years. While it is true that the United States’ quality of care is world-class, the current barriers to entry in our healthcare system prevent many from receiving the care they deserve. We often hear stories in the media of people, especially seniors, skipping medical care and medication because of its high cost.

Two areas of healthcare that are most in trouble in terms of accessibility and cost are the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicare. The ACA plans are unaffordable, and Medicare is on the verge of insolvency beginning in 2033.

While there is intense debate between the two political parties over who should pay the ACA premiums — the individual member or the taxpayer — neither party appears to be addressing the real problem. The ACA is in crisis and dysfunctional. The services it offers are limited in terms of quality and accessibility, and its costs are out of control. For example, Access Health CT, the Affordable Care exchange in our state, is neither affordable nor accessible.

President Barack Obama’s declaration, “If you like your doctors, you can continue seeing them,” turned out to be a false promise. The ACA is not affordable, and its quality of care and provider network are limited. In our state, you cannot go to an out-of-state hospital, and many of the top providers inside the state do not accept ACA insurance plans. For example, the highly recognized Connecticut-based Hospital for Special Care (HfSC) does not accept Access Health CT insurance.

To understand the problem with the ACA, let’s dig a little deeper and examine our own state’s ACA exchange in more detail. Picking an insurance plan on the Access Health CT website is like shopping for a mattress sold at different stores under different names and model numbers, with slightly different bells and whistles. Wherever you shop, the mattress is basically the same, and the minor feature tweaks at different locations are seemingly designed to make it difficult for customers to compare between stores.

While there are two managed care companies (MCOs) — Anthem and ConnectiCare — and 20 plans to choose from on the exchange, the plans offered by each MCO are almost identical, and the different plan options, except for some minor tweaks, are basically the same. If you analyze the various plans, it will quickly become apparent that, by its very design, Access Health CT is basically nothing more than a broken single-payer system. The options on the exchange are like 20 variations of the same lumpy mattress, with minor variations in pricing and covered services.

On the Access Health CT Exchange, you genuinely have only two options— you either pay more in premiums and have a lower deductible, or pay less in premiums and have a higher deductible. Whichever plan you choose, the bare-bones provider networks, the limited quality and accessibility of care, and the overinflated costs are practically the same. While each plan might have different copayments and deductibles, whichever plan you ultimately choose, they are basically the same in terms of their restricted in-state-only provider networks, limited quality and accessibility of care, and unaffordable costs. For the most part, it all boils down to a simple equation: the higher the premium, the lower the out-of-pocket cost; the lower the premium, the higher the out-of-pocket cost.

To illustrate my point, let’s look at the ConnectiCare plan options for a family of four residing in Fairfield, with parents ages 63 and 60, and kids ages 21 and 24, with an Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) of 130,000. The most affordable plan is the “Value Bronze HSA plan.” The annual premium for this plan is $54,272.52, the family deductible is $13,000, and the max out-of-pocket is $14,450. In this scenario, the member is responsible for a total out-of-pocket expense of $68,722.52 before reaching 100 percent reimbursement.

The other option is the “Value Gold Standard POS.” The annual premium for this plan is $83,272.92, the family deductible is $2,400, and the max out-of-pocket is $14,750. In total, the member is responsible for an out-of-pocket expense of $98,023.88 before the insurance provides 100 percent reimbursement.

Looking at these numbers, it is pretty confusing as to which plan is better: the Bronze or the Gold. One would expect the Gold plan to provide superior coverage to the Bronze plan. Yet, when you analyze the data, which is perplexing and challenging to understand, the opposite of what one would expect turns out to be true: the Bronze plan is less costly for practically the same benefits.

With the Gold plan, you’ll end up paying over $29,000 more for the same coverage provided by the Bronze plan. For this family of four, with an AGI of 130,000, even if they choose the more affordable Bronze plan, once they have met their out-of-pocket cost, at least 53 percent of their total income will have gone toward healthcare expenses.

It is not a secret why the ACA is broken — these plans are run by large for-profit corporations that are more concerned with their stock price than with accessibility and the quality of care.

For years, managed care companies have squeezed providers on reimbursement rates and restricted care under the guise of “medical necessity” to increase their own profits. What has made matters worse is the rise of large Integrated Delivery Networks (IDN). These are hospitals and providers that have formed large provider companies to combat the financial pressures of the managed care industry.

In Connecticut, there are also only two large Integrated Delivery Networks (IDNs) — Yale New Haven Health System and Hartford Healthcare. These two systems, over the past several years, have aggressively expanded, buying up hospitals and medical practices to gain leverage in negotiations with managed care organizations. With the IDNs’ newfound negotiation clout, the MCOs’ only remaining means to increase revenue is to raise member premiums substantially.

This year, the state of Connecticut approved a 25% premium rate increase for ConnectiCare. Since the start of AccessHealth CT in 2014, the average premium cost has increased by almost 300 percent. Yet the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which tracks overall inflation in Connecticut, has increased by only 35–45% since 2014, a fraction of the rise of ACA premiums.

Unlike ACA enrollees, Medicare beneficiaries do not have problems with premium costs, accessibility, or the quality of care. Eighty-six percent of Medicare participants say they are happy with their plans. In my practice, I often hear seniors’ joke: “The only benefit of getting old is my Medicare.”

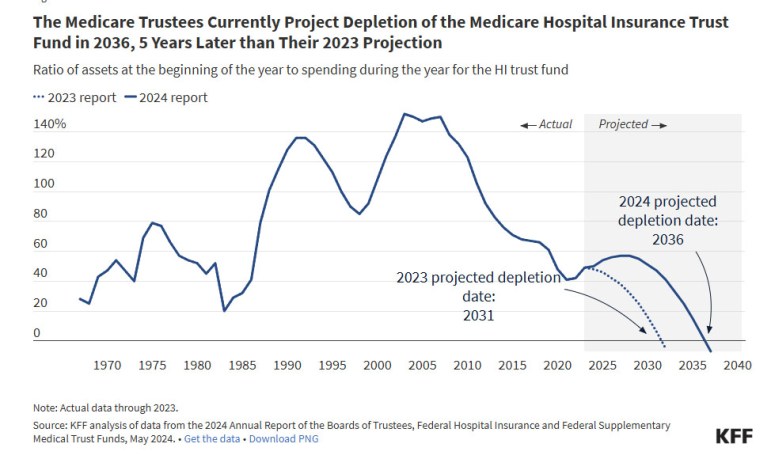

The problem with Medicare is that its fiscal foundation is on the verge of collapse. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Medicare trustees’ data, if Congress does not figure out how to increase funding, Medicare will become insolvent by 2036.

While many people believe that a nonprofit single-payer system is the way we need to go, how we get there is rarely discussed by politicians on either side of the aisle. The debate between who should pay these outrageous ransom-like fees —we the individual or we the taxpayer — is nothing more than bipartisan smoke and mirrors spun by politicians who are in bed with insurance lobbyists.

There are clear steps our government can take to begin to heal our sick healthcare system. What I propose in this article is a plan that would significantly reduce healthcare costs and keep Medicare solvent for another 20 years. What I am suggesting is the addition of a new tax bracket for married couples earning more than $1 million per year. If the top 0.5 percent of the population (approximately 65,000 households) were to pay a tax rate of 47.7 percent, rather than the current marginal rate of 37 percent, on earnings above $1 million, not only would Medicare be solvent for another 20 years, but we could lower the age of Medicare eligibility to 50.

Lowering the Medicare eligibility age to 50 would be financially beneficial for almost everyone —the government, corporations, healthcare providers, and individuals of all ages. It would also improve the quality of care and accessibility for the entire United States population. The only ones who would lose in this scenario would be the managed care industry and the politicians who accept lobbyist funding.

ACA premiums would decrease significantly because members aged 50-64 are the highest cost enrollees in these plans. If the Medicare eligibility age were lowered to 50, it is estimated that over 25 million would exit the ACA. The ACA risk pool would become younger and healthier,and claim volatility and costs would decrease significantly, becoming more stable and predictable.

Since members ages 50-64 have the highest premiums and out-of-pocket costs under the ACA, adopting this program would eliminate the financial catastrophic risk for millions. The government would save billions in subsidies, since approximately 25 percent of subsidy recipients are in this older age group. Hospitals would see modest increases in volume from newly eligible adults. They would also benefit from more predictable Medicare rates and from reduced burden of absorbing the cost of treating patients without insurance coverage. Most importantly, rural hospitals, which are currently facing financial ruin, will be able to stay open because of the stability and increased percentage of insured patients.

Such a change in our healthcare system does not have to be done all at once; it can be done gradually. For example, if the Medicare eligibility age were lowered at first to 60 rather than 50, the required surtax for married couples earning more than $1 million could drop from 47.7% to 45.6%. This would significantly reduce overall healthcare costs and allow Medicare to remain solvent for another 20 years.

The problems in our healthcare system didn’t happen by accident —they’re the result of policies that put insurance companies and corporate profits ahead of patients. The ACA has become expensive, restrictive, and unreliable, and Medicare —one of the few programs people actually trust— is heading toward insolvency if nothing changes.

But there is a realistic way forward. By slightly increasing taxes on households making over a million dollars and lowering the Medicare eligibility age, we could stabilize Medicare for decades, dramatically lower ACA premiums, improve access to care, and reduce financial strain on families, hospitals, and the government.

This isn’t a partisan solution; it’s a practical one. We can either stay with the current broken system —sky-high premiums, limited networks, and growing instability— or we can make targeted, sensible changes that strengthen Medicare and make healthcare more accessible and affordable for everyone.

The path is obvious. What we need now is the will to take it.

Martin H. Klein is a clinical psychologist practicing in Westport. He is the author of a new book entitled: Rethinking Cognitive Behavioral, Psychodynamic, and Existential Therapy: A Philosophical Framework for a Unified Therapeutic Model.