Some 50% of people who are incarcerated in Connecticut are back in prison within three years of release.

People reentering their communities after being in prison often struggle. They have difficulties being hired, finding housing, and receiving the support that they need. Without stability, they fall back into the circumstances that led them to being incarcerated initially, and they are then rearrested.

The cycle of recidivism cannot be blamed on the people caught within this system. Rather, we as taxpayers and voters must realize the prison system that we fund and enable is not fulfilling its supposed purpose.

The CT Department of Correction’s stated mission is “to be a leader in progressive correctional practices and partnered re-entry initiatives to support responsive evidence-based practices geared toward supporting reintegration and reducing recidivism under the Department’s supervision.” Yet the state of Connecticut has one of the highest recidivism rates nationally. As community members, voters, and taxpayers, we have a duty to demand better of our state’s Department of Corrections so that people who are incarcerated will not be stuck in a lifelong cycle of recidivism.

Fortunately, we already have a blueprint of how to do this.

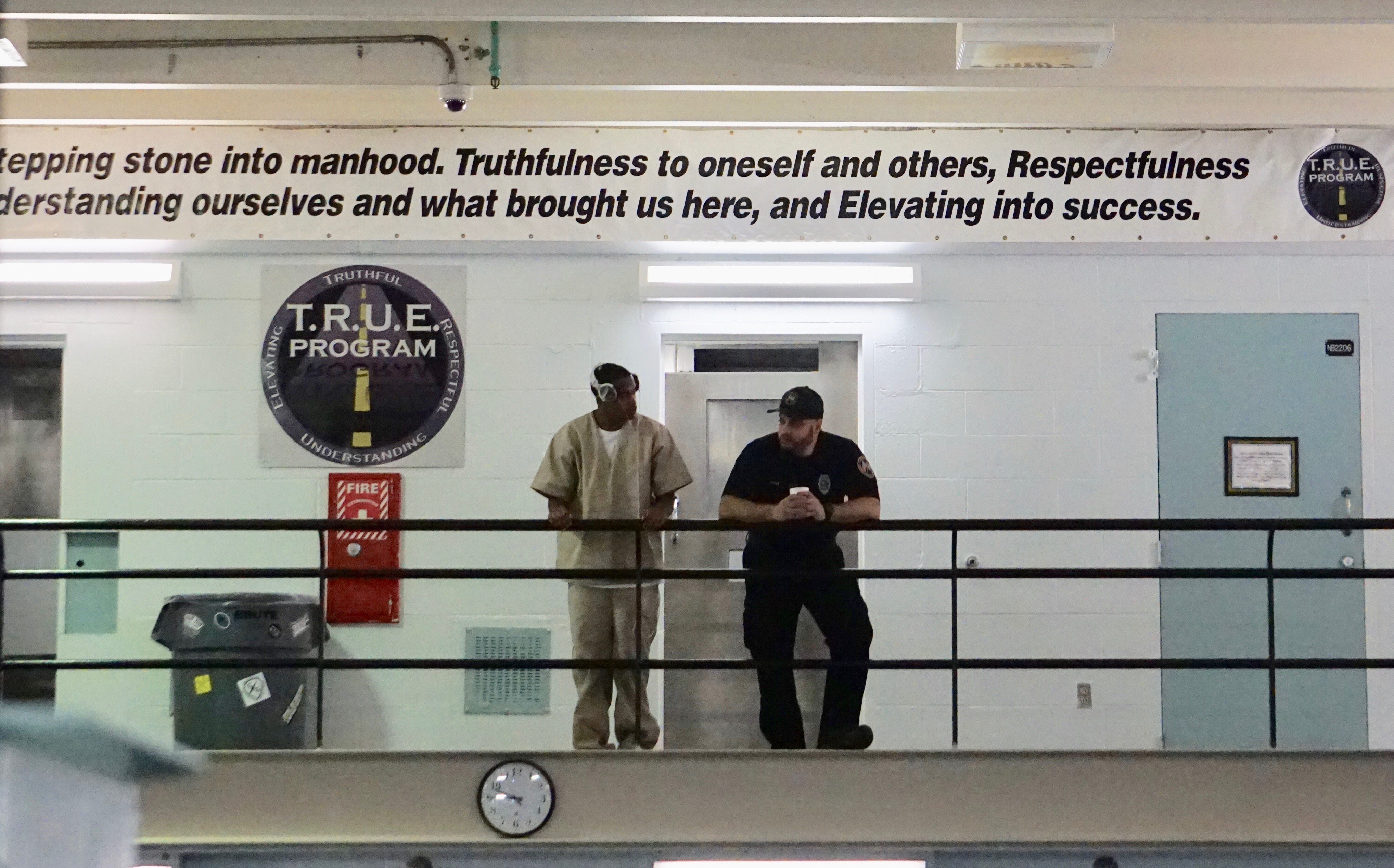

Established in 2017, the T.R.U.E. (Truthfulness, Respectfulness, Understanding, and Elevating) unitat Cheshire Correctional Institution offers a potential pathway to lower recidivism. Modelled after the German prison system, this program pairs 18-25 year-olds serving shorter sentences with older mentors serving life sentences to help the younger men prepare to reenter their communities. Both mentors and mentees voluntarily apply to participate in the program, and mentors complete training in therapeutic practices before they are partnered with a mentee.

They live in a unit of the prison together with specially trained correctional officers. Every morning, participants check in with each other about their goals for the day, and mentors have conversations with the younger men about the difficult realities they will face in reentering their communities. They have access to a library, a barber shop, and a room with chalkboards to share ideas and concerns. They also participate in classes and workshops on anything from slam poetry to crafting a resume and preparing for job interviews. Participants are given mock salaries, pay mock taxes and rent, and are fined if they violate a rule.

In short, they actively work toward their successful reentry into society.

The mentoring relationship between the younger and older participants centers on healing, discipline, accountability, and growth. “The important thing about this program is we try and hold them accountable for everything they do,’” said one mentor in the program in an interview with the Council of State Governments Justice Center. Mentors and mentees work together to build emotional skills and plan for reentry to break the cycle of recidivism.

Voters and policymakers need to prioritize expanding this model to other prisons throughout the state, so that others might benefit from this programming in the same ways T.R.U.E. participants have.

In T.R.U.E., interactions between participants and correctional officers are much less punitive than in the prison population more generally. Some may think that correctional officers would not want to participate in this program because it is different and less punitive than their normal approach. However, staff at Cheshire were excited to participate in this program. According to an interview with Scott Semple, a former Commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Corrections, over 100 staff members applied to work on the T.R.U.E. unit.

Instead of sending someone to solitary confinement or taking away their commissary access, correctional officers who notice that a participant has violated a rule will bring this to the mentors. Often, there will be a group discussion between participants about how to address the violation and what consequence the person should have, which might include extra chores or paying a fine.

The impact of the T.R.U.E. program is evident. Only 21% of mentees have returned to prison,which is a steep drop from the state’s general reincarceration rate of 50%. Although the program has been successful since it was founded, Connecticut has not expanded this model to many of its other prisons across the state. Thus far, only one other prison, the York Correctional Institution for women, has adopted a similar program.

Funding has been a significant barrier that prevents the broader expansion of the T.R.U.E. model. However, investing in expanding the program would lower the overall costs of incarceration considerably. There are significant costs associated with reincarcerating 50% of those released from prison within three years. The Council of State Governments Justice Center calculated that Connecticut spent over $100 million on reincarcerating people in 2022. T.R.U.E. reduces reincarceration from 50% to 20%, and adopting these types of units more widely in the state would help cut the high costs of continually reincarcerating people.

The model of the T.R.U .E. program offers a promising pathway to reduce the issue of recidivism in our state. In an interview, one T.R.U.E. mentor reflected on how he would convince skeptics that this program is worthwhile, saying “I would ask those people in society to please try to walk in someone’s shoes who watched their father get killed, who watched their brother get killed, who watched their mother do drugs. And think, what type of person would that child grow up to be?” He emphasized the T.R.U.E. program’s focus on accountability and discipline, saying “I’m not asking you to start paying taxpayer dollars to give people the world. Let them earn it. But see if it [programs like T.R.U.E.] works. We’ve tried everything else, haven’t we?”

Caitlin Doherty is a senior at Trinity College majoring in Public Policy & Law and Human Rights.