|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

On a welcome muddy day in January — a warmish respite between polar vortexes and snowstorms — a small work crew hoisted 20-foot long steel pipes into a hole being bored hundreds of feet deep in the scraggly field across from Union Station in New Haven.

With old-school technology, the pipes were welded together and pushed down the hole where they are slated to form the core of an energy technology that is at once new-age and as old as the hills.

This is geothermal technology.

A clean energy option that the Trump administration somewhat supports, it harnesses the heat amassed over hundreds of millions of years beneath the earth’s surface to provide heating and cooling, hot water and electricity.

But not all uses are suitable everywhere. There are different means and different costs for tapping that heat. And as old as geothermal is, its implementation is still being refined.

“What you’re seeing right now is they’re installing the steel casing,” said Chris Treiling, a geotechnical engineer with CDM Smith, the company doing the on-site work at Union Station. “They drilled through the overburden, which is sand, gravel, clay, into the top of bedrock, which is a little over 300 feet. And now we’re installing the casing, which will stabilize that overburden material and continue drilling down to the target depth of little over 800 feet.”

This borehole, as it is called, even though it’s considered a test hole, eventually will be looped into the full system for heating/cooling and hot water for the train station and about 550 yet-to-be-built mixed income apartments.

“The benefit of this is you get information about the soil that will assist us with further refining our models and designing the system, and you also get information on what type of drilling conditions you should be prepared to encounter, because there’s always uncertainty when you go out to any of these projects,” Treiling said.

He’s found that out already. This is actually the second attempt to drill the second of two test boreholes. CDM had to bring in a heavier duty drill when the first attempt ran into some difficulty.

They were not looking for an Old Faithful.

“That’s what people picture when you say geothermal; they picture geysers,” said Julie Fosdick, a geoscientist at the University of Connecticut.

Nope — you just have to dig. The heat is there; no spouting steam and water necessary.

Geology basics

Heat is underground everywhere on earth, and it’s residual from earth’s formation, said Fosdick, who studies long-term rock thermal histories.

“There is so much heat in the earth — that is what makes geothermal fantastic,” she said, explaining that heat is stored and flows through different rocks in different ways with different conductivity. “That heat structure is not at risk of being depleted. So that is a total plus about geothermal.”

But heat varies from place to place in potency, accessibility and depth. It’s most accessible and hottest in younger, more volcanically active areas such as the western U.S. — California, the Great Basin, Nevada. These are places where there’s active faulting and earthquakes and also active volcanic activity that brings more of the deepest, hottest heat to the surface.

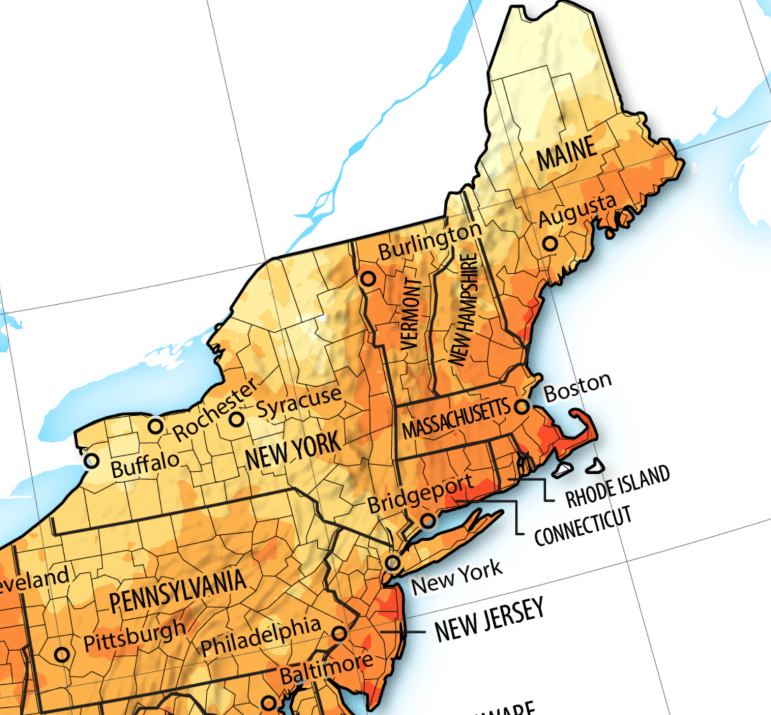

A national map released by the federal Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Lab, NREL, recently renamed the National Laboratory of the Rockies by the Trump administration, shows the intensity of geothermal resources as deep red from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific coast. New England is a much lighter orangey-yellow.

That’s because New England doesn’t have active tectonic or volcanic activity as it did hundreds of millions of years ago, Fosdick said. “We just have a much older geologic history here in the Northeast. And it’s been 150 million years since we had active volcanoes,” she said.

“That would have been the prime time to put in your geothermal system,” she joked.

Fosdick said Connecticut has a lot of variability in its rocks, including granite and gneiss. “These are hard rocks that you would drill into, compared to, say, the softer sediments that are along the coastal regions, that are along the Connecticut River Valley,” she said. “For different kinds of geothermal systems, you want rocks with slightly different properties to transmit the heat versus, maybe, store the heat.”

But out west, volcanic fissures and moving tectonic plates — especially ones that are moving away from each other — let below-surface heat out, making it hotter and easier to access.

These different geologies have a bearing on what types of geothermal systems are feasible.

“Knowing the rock types and knowing the properties of those rocks really does matter for predicting what’s going to work,” Fosdick said.

Technology basics

Geothermal heat in the west is pervasive enough to make electricity from it. That means getting hot water and steam from deep underground 24/7 to run power plants. This has been done for decades.

The most updated technology is called enhanced geothermal systems, EGS. It involves updated drilling techniques that require fewer boreholes. Some think it may eventually be feasible in the eastern U.S., including Roland Horne, an earth sciences professor at Stanford University who has studied geothermal energy for decades, with a particular focus on its use for generating electricity.

“Not yet,” he said of EGS suitability in the eastern U.S. “But it’s sort of looking a lot more promising than it ever did.”

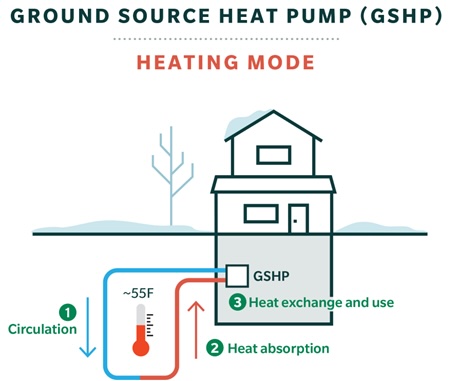

In the east, including New England, he said ground source heat pumps, also called geothermal heat pumps, are the name of the game.

They are used for heating/cooling and often hot water, not for electricity, but they help take pressure off the electric grid, especially during cold temperature extremes when electricity and heat often compete for a finite amount of natural gas.

“Ground source heat pumps are kind of the main event for geothermal in the eastern states, and very effectively so,” he said.

Ground source heat pumps are at once different and the same as the more commonly used and known air source heat pumps. Those are the ones that look like big fans typically seen outside homes.

Both types operate by bringing heat into a building in the winter and letting it out in the summer. Air source heat pumps use the air temperature to regulate that process while geothermal heat pumps use the ground temperature, which is much steadier than the air.

The geothermal that individual homeowners mainly use, and the geothermal system planned for the New Haven project, run liquid — treated with an anti-freeze type substance — through a loop that recirculates the liquid. It’s called a closed loop system.

“It is a confusing terminology, because geothermal to us in the West Coast means the heat of the earth. A ground source heat pump doesn’t really take advantage of the heat of the earth at all. It just uses the ground as a thermal sink or source,” Horne said. “They’re not really extracting the heat of the earth. They’re just borrowing it for a while and putting it back during the summer.”

There are downsides to both geothermal systems. A closed loop system for heating and cooling, while emitting zero emissions and more efficient than an air source heat pump, has a higher upfront cost and can be harder to site, especially in cities and other dense population areas.

EGS has some carbon emissions. And out west, geothermal drilling, even taking advantage of the existing volcanic activity, can cause earthquakes.

“There are seismic events generated along places where there’s enhanced geothermal fluid injection to create those cracks and fractures,” Fosdick said. “These are tiny earthquakes, small earthquakes.” She said it would be important to keep drilling away from some of the ancient faults.

Connecticut, while not seismically active, does have one area around the southeastern town of Moodus that gets tiny earthquakes (as well as noises that seem to accompany them). The NREL map shows that region as the darkest coloring in the state — meaning it’s most conducive for geothermal resources.

It is also, not coincidentally, adjacent to the shoreline and the Connecticut River. Wet ground conducts heat better than dry ground.

That could prove beneficial for the New Haven project, which is in an area prone to flooding.

“Wet mud has much better thermal properties, and that’s partly why the coastal region has those brighter red spots,” Fosdick said referring to the NREL map. “Because as you get along the coast, the rock types change a little bit. But, yeah, heat capacity in wet materials is much better.”

“Now, you wouldn’t want to have your machinery in flood zone,” she said. Especially salt water.

The New Haven plan

The plan for the New Haven train station and apartment project is what’s often called “networked geothermal.” To oversimplify it, this means it’s a closed loop system that accesses the underground heat, which then essentially is split apart at the surface to be used by different entities within the project. Heating and cooling levels can be regulated in individual apartments and all other units.

“There will be an array of geothermal wells that are connected by lateral pipes. And there will be a central pump system that will circulate fluid through those wells and lateral pipes,” said Steve Winter, who is New Haven’s executive director of climate and sustainability as well as a state representative.

The two test boreholes provide a look at the thermal performance data from both to determine what the final design of the system will be, said Treiling of CDM, which is also creating that design.

He said the first borehole is showing higher thermal conductivity because it hit bedrock at around 210 feet below the surface. The second didn’t reach bedrock until around 320 feet. The first borehole ultimately went down to 1250 feet through a greater percentage of bedrock than the second, which only went to 850 feet. He said so far the heat that can be pulled from the formation is consistent with what the original assumptions were based on the geology of the site.

The initial focus in New Haven will be heating and cooling for the train station. But the ideal operation is to have the residential components and the station operating together. It’s a concept called “diversity of load,” said John Ciovacco, president of Aztech Geothermal, the company overseeing the project on behalf of New Haven.

That’s when there is a variety of buildings that are heating and cooling differently from each other. That diversity tends to benefit the underground discharge and collection of heat — what Ciovacco calls the thermal battery — because they can offset each other. The needs of the station and housing are different enough that that is likely to happen.

“Union Station will have a different what’s called a load profile, a different heating and cooling sequence than the Housing Authority buildings will,” Ciovacco said. “As a result, if we had to just do a bore field for the housing authority and a separate bore field for Union Station, we would need more boreholes in total, but we can take advantage of some of those offsetting loads and decrease the infrastructure by combining the buildings together.”

Which, of course, means spending less money up front.

The overall cost for all the underground geothermal work and retrofitting of Union Station is $16.5 million. The cost of the apartment buildings, which will also have ground floor commercial and community space, will be separate.

The city finally has $9.5 million in hand. The money had been approved and obligated by the Biden administration, but the Trump administration then froze it before eventually releasing it. There’s another $7 million in cost share from the city. But the city doesn’t have that on hand. So Winter said they are negotiating a bridge loan from the Green Bank to cover the city’s share until the project receives its federal geothermal investment tax credit. The city will use that to repay the loan.

The Trump administration has discontinued that tax credit for geothermal residential projects — the kind homeowners would purchase. But it remains operative until the mid 2030s for commercial projects.

While the Trump administration has voiced support for geothermal and has made some money available, the DOE told the Connecticut Mirror that its office of geothermal does not currently have any open funding opportunities.

There is also some concern that the administration’s focus will be on EGS, not projects like New Haven’s.

In an email, the DOE said: “The Office of Geothermal is currently funding research and development across a span of geothermal activities, including power production (enhanced geothermal systems and conventional hydrothermal), energy storage, and thermal use. Future solicitation topics will be determined according to Administration and Office priorities, research and development needs, and Congressional appropriations.”

To be clear, geothermal has been in use and researched for decades in the U.S. Ciovacco at Aztech has overseen geothermal projects in any number of apartment and other buildings, as has Treiling at CDM. And the two companies have done some of that together, most notably in New England — a networked geothermal system in Framingham, Mass.

But it was far from the first such system in the region.

Framingham and elsewhere

“There’s a whole lot of network geothermal systems on campuses,” Ciovacco said, rattling off a list of schools around the country, some of which have been using geothermal for well over a decade. In Connecticut, UConn and Yale are moving ahead with systems. “The networking part of it is not new,” he said.

Most are closed-loop systems like New Haven’s and Framingham’s. But at Cornell University, for instance, the school is planning a direct source geothermal heating system in which buildings get heating sources directly from the ground.

What was touted as new in Framingham was that the system was being spearheaded and owned by a regulated utility — Eversource — except that wasn’t exactly new either.

Back in 2016 in Riverhead on Long Island, National Grid did the same sort of thing, though much smaller and more homogenous. It was just 10 small homes.

New Haven won’t be utility-owned, but Ciovacco said his company is presently working with about 10 utilities. Eversource was just first out of the gate.

“It’s not a technology risk. It’s not a first ever to connect a bunch of buildings together and take advantage of diversity of load. It’s more of a business model that we’re trying to develop for these systems and the regulatory process makes that much more complex,” he said. “It’s not like we’re afraid that we won’t be able to heat and cool Union Station. We’re good.”

But there were learning curves in Framingham, and there may well be some as the New Haven project progresses.

Framingham includes 36 buildings. Most are residential; five are commercial. That diversity was part of the criteria when Eversource first proposed it in 2019, said Liam Needham, Eversource’s director of thermal solutions.

Eversource faced a number of new challenges beyond the company’s standard role of delivering power to homes and businesses. In this project, they were responsible for the actual equipment inside people’s homes — a first for them, Needham said. He and others pointed to drilling challenges with limited space and experience. Unlike other parts of the country where oil and gas drilling, which use the same techniques as geothermal, has been around for years, drillers aren’t even readily available in New England.

One of the biggest challenges, he said, was retrofitting homes in New England’s notorious old housing stock.

“We ran into everything you can imagine, from asbestos, mold, challenging installations, houses that weren’t designed to have duct work or central air. A lot of the homes had baseboard heating. Some had steam radiators, and we had to take those out,” he said.

That said, Eversource is looking to expand the project as well as tackle others in Massachusetts. In Connecticut, he said, Eversource included a framework for geothermal in a 2024 rate case.

“We are open to moving forward with those conversations with Connecticut, as long as we can get some certainty around cost recovery for a project,” he said. “We didn’t quite get that clarity in the outcome of the rate case, but we’re willing to do it and talk about it.”

Connecticut has been open to geothermal and in fact received federal funding in 2023 to explore the potential for geothermal in a 123-unit affordable housing complex in Wallingford known as Ulbrich Heights. But the cost, along with the homogeneity of the load and the fact that the units were spread throughout 38 buildings, resulted in the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, DEEP, deciding not to pursue DOE funding.

Aside from the university and New Haven networked systems, a state map shows individual commercial geothermal heat pumps in municipal buildings, schools and elsewhere around the state. Homeowners are using them, though not anywhere near as often as they’re using air source heat pumps.

A spokesman for DEEP said geothermal heat pumps are supported by the New England Heat Pump Accelerator and that DEEP is also evaluating options to advance feasibility studies of thermal energy networks that include geothermal networks.

Kat Burnham, a senior principal with Advanced Energy United and the group’s Connecticut lead, noted that geothermal is really a local energy source.

“We’re in an energy affordability crisis. In both our heating sector and our electric sector, folks are having a hard time affording their bills, and instead of having imported fuels like natural gas or oil, where those expenses are going up, these systems allow not just for a reliable energy system, but some price stability as well,” she said.

It’s a sizeable investment with a longer payback.

But, she said, “You’re investing in a reliable, predictable system that is not subject to foreign war price spikes, not subject to tariff price spikes.”

And it’s under our feet.