At least once a year, parents of students with disabilities enter a meeting with school district leaders to discuss their children’s development and any changes to their individualized education plans, which spell out what services students will receive that school year.

State guidelines say parents are “an equal member” of the Planning and Placement Team — a group also made up of teachers and school administrators that determines the educational needs of a child — but the families in the room and hired experts that help them navigate the special education system say otherwise.

They describe the meetings as a battlefield.

They say the encounters often end with ignored concerns, belittlement or intimidation on the part of school officials toward parents.

Parents, lawyers and special education advocates say the problem isn’t the educators in the classroom but instead local administrators who create a relationship that’s lacking in partnership and transparency.

“There’s hundreds of cases of poisoned relationships between schools and parents,” said Andrew Feinstein, a special education attorney who’s been practicing for over 30 years. “[Districts] think they absolutely understand the child, but they don’t understand them at all. … It’s this kind of arrogance of expertise … where they’re going through the motions and talking to parents like, ‘We’re doing what we have to do. … And our hope is the parents agree with us, but if they don’t? Well, we still know what’s right.'”

In a statement to The Connecticut Mirror, the state Department of Education stated that “positive and proactive communication between the school district/program and the parent is essential to effective outcomes for students with disabilities.”

Matthew Cerrone, the education department’s director of communications, also outlined state resources, including the Bureau of Special Education Call Center and the Connecticut Parent Advocacy Center, which can help parents understand procedural safeguards, file complaints and other “options to help families and schools resolve disputes.”

But stakeholders argue that more has to be done.

Legal and educational jargon, hundreds of pages of pamphlets and interactions that make parents feel like there’s a clear power dynamic make it difficult to meaningfully engage in the meetings with districts, stakeholders say. It’s also difficult to know the full extent of rights and what you can challenge, ask for or negotiate with the district educating your child.

“It’s hard enough to have a child with a disability, then, on top of that, to have to be expected to know what you don’t know about education. … Schools are set up to confuse parents on every level,” said Kit Savage, the managing director of Savage Advocates and mother of two children with disabilities. “[The system] is stacked against them. It’s set up to fail parents who don’t have outside support.”

“When you walk into a room as one parent with a room full of professionals who are on the same team, it feels intimidating. It’s intimidating for anyone. They work for the same district, they’ve been in contact and communication about the matter, and you have an imbalance of information,” said Kathryn Scheinberg-Meyer, an attorney at the Center for Children’s Advocacy.

Scheinberg-Meyer said there’s times where district leaders may speak over parents or give families “the runaround,” when they ask for certain information, data or request more services for their child.

Parents across Connecticut say meeting with districts is a frustrating process that leaves them feeling that the education leaders they once may have trusted are cheating some of the highest-need students out of equal access to public education.

Are you a parent or educator who participated in a recent PPT meeting in Connecticut? What was your experience like? Share them with us here. Submissions could be published in CT Mirror’s Viewpoints.

But Fran Rabinowitz, the executive director of the Connecticut Association of Public School Superintendents and a former superintendent in Bridgeport and Hamden, says most districts are doing “the very best they can” amid a teacher shortage and increasing costs for special education services.

“I know Waterbury was down about 55 special ed teachers,” Rabinowitz said. “There’s no way that you can provide the full services that you want to provide. And the caseloads have become much higher — I worry about that.”

Rabinowitz said she hasn’t heard superintendents directly speak about complaints between families and administrators, but if it’s occurring in many districts, the concerns from parents are “reasonable.”

“If we’re down all these special ed teachers, para[educators] and school psychologists, it’s got to have an impact,” Rabinowitz said, adding that several districts are now hiring contractors to make up for the staffing challenges, which affects school budgets and rising special education costs.

Connecticut public schools spend nearly $2.7 billion annually on special education services. For some districts, special education costs make up a significant portion of their budgets. For example, in Bridgeport, which educates the most students with disabilities in the state, over 26% of the total expenditures go toward special education for things like teacher salaries, transportation or outsourcing to other schools if the district can’t meet the students’ needs.

A new portal on the education department’s website that went live in late April will now make state complaints publicly available. A handful of complaints filed in the first few weeks, mostly pertaining to failure to properly implement an IEP, have been uploaded so far from Danbury, New Haven, Wallingford, Bristol and the Connecticut Technical Education and Career System.

Formal state complaints can be filed by families or organizations if there’s a belief that a “local school district or other public educational agency has violated a requirement of state special education law,” or federal law, according to guidance by the state education department. The Bureau of Special Education is then required to investigate and issue a findings letter within 60 days.

The state Department of Education did not respond to questions asking how common complaints of inadequate services are, why the process between families and districts may feel combative or what factors can make it difficult for a district to meet special education demands. Interviews with parents across the state from some of the wealthiest districts, like Woodbridge, to towns like Watertown, to cities like Bridgeport and suburbs like Enfield, however, point to enough similarities to indicate that the issue may be widespread.

‘It’s like a battlefield’

When Jennifer Cotto prepared for her PPT meetings with Watertown Public Schools, nervousness would kick in a few days before.

She called the meetings “anxiety-ridden.”

She would make a list of all of the questions and concerns she had about her 4-year-old daughter Isabel’s pre-K education plan. Sometimes the preparation would be several pages long. She just wanted to stay organized.

Before the meetings, Cotto would sit in her car and take a few deep breathes to make sure she could enter the meeting calm and collected.

“This is my daughter, and I will go to war for my children, but I don’t want that to be the first impression that they get from me,” she said.

Cotto, who’s worked as a case manager for over 15 years and is currently studying for her master’s in social work, is familiar with the system and how “there’s nothing easy about it.”

Her professional background has prepared her to expect the worst.

She anticipated her first PPT meeting to be painful after all her experiences advocating for other families “many, many, many times” over the years.

But when the meeting was easy to set up and went well — just introducing herself and her child and setting a time for testing — she was hopeful maybe her case would be different.

That dream was short-lived. The second meeting was full of disagreements about the services her daughter needed.

“When you’re a parent of a high-functioning child, you’re always being told ‘Well, it’s not enough of a disability to get the help you’re looking for,’ or you have to argue your way to get what you’re looking for,” Cotto said, adding that despite her daughter being medically diagnosed with autism, the district wanted to limit her IEP “as developmentally delayed.”

Watertown Public Schools did not respond to requests for comment.

“My school district tried to tell me … she might grow out of this,” Cotto said. “But we were quick to say ‘No. You don’t grow out of autism.’ She will always be on the autism spectrum. She will learn, she will grow and eventually be a very productive kid, but … you can’t label her as developmentally delayed to keep her from getting the services she needs. It’s ridiculous.”

The disability classification could change the services a student is provided. A child on the autism spectrum would have access to behavioral therapy and one-on-one instruction, while children diagnosed with learning disabilities may receive limited services, like additional time for testing.

“It’s this resistance to give complete services, well-rounded services,” Cotto said.

After her daughter’s medical diagnosis, Cotto got her into private occupational therapy. Cotto said the district told her that they didn’t believe her daughter needed physical therapy services at the school because she was doing well holding a pencil and other tasks.

“But the only reason why she is doing as well as she is, is because I have a private OT outside of the school,” Cotto said. “The school is looking at it as ‘How is this impacting education right now, right in this moment?’ And my thing is, how is this impacting education long term? So if I were to stop giving my getting my daughter outside OT right now — in six months, how will she be?”

By the third PPT meeting, all held within the first year of enrollment in the pre-K program, Cotto said she felt the district was just looking at her daughter as a “price tag” after she said the district refused to provide 30 minutes of physical therapy a week.

“You’re not willing to give her 30 minutes of your services, just so we can say, ‘At least we try it and then we determined it’s unnecessary’?” Cotto said, adding that it would have been a different story if the district had made attempts to compromise rather than completely shut down the suggestion.

“It’s literally like a battlefield. It’s just so awful and feels like you’re constantly going to war,” Cotto said. “The way it was handled was awful. It really did feel like ‘Sorry, your kid’s not worth it. Your kid’s needs are not enough for us.'”

Cotto’s family left Watertown and relocated to Ansonia this spring.

‘The squeaky wheel gets the grease’

After her child was enrolled in public schools for 13 years, Shari Jackson said, she can’t wait for that last PPT meeting at the end of the year.

As a mother, she’s going to be leaving the system “battle-scarred,” she said.

“Having a child with special needs is not the hardest thing, but having a child with special needs go through the school district is the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life,” Jackson said.

Throughout her adopted daughter’s K-12 educational career, spent both in Wethersfield and Enfield, there would be some days where Jackson would stay up until 2 a.m. preparing for meetings.

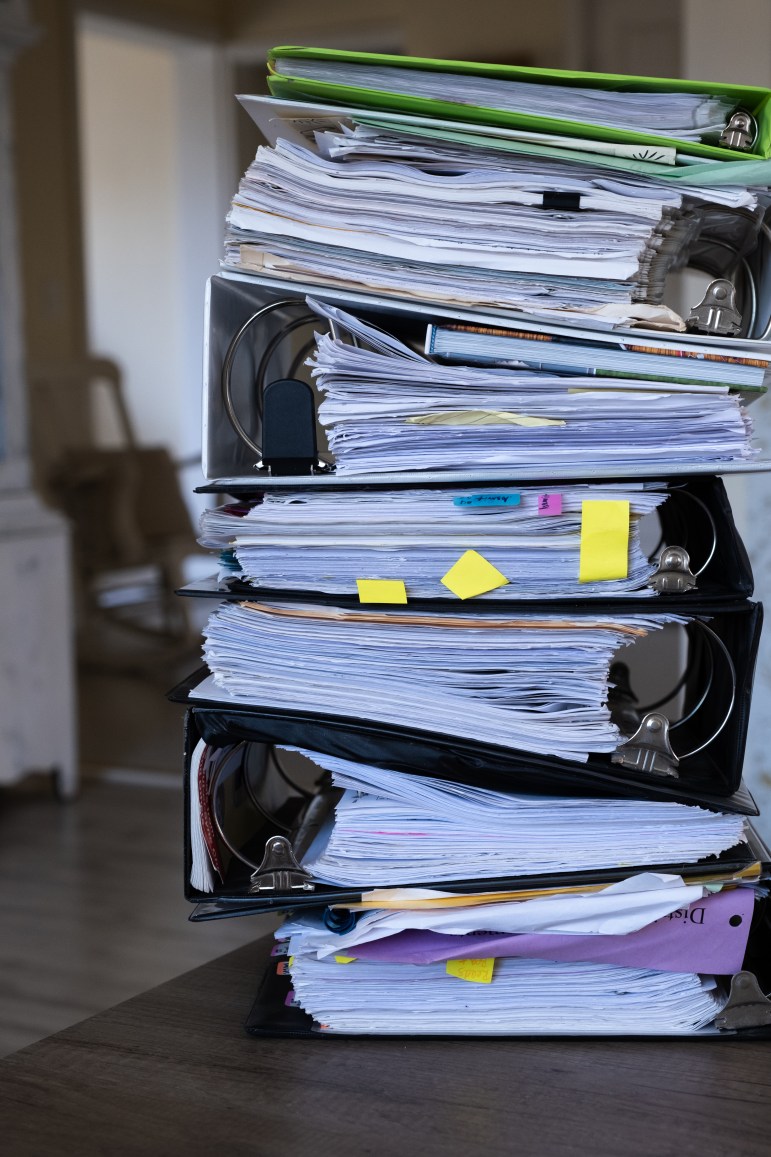

There were usually two meetings annually, but during the worst disputes with the districts, it increased up to five or six three-hour meetings, Jackson said, adding that she would bring a handful of 4-inch binders to several of them — full of research, questions and proof that the district “was not servicing her correctly.”

If it didn’t go well at the meeting, she would follow up with a call to the principal. If that didn’t get anywhere, she would call the superintendent. If worst came to worst, that meant threatening to go to the local board of education.

And now her daughter, who has dyslexia and a sensory processing disorder, is set to graduate from Enfield High School in a few weeks as an honor-roll student. She plans to attend Bay Path University with a $96,000 scholarship in the fall — something Jackson believes was only possible because of how strongly she advocated for her all those years.

“My daughter was the one in the school who was tearing the room apart, and biting, and throwing things, and running away and doing all of those kinds of things because her disability was so poorly understood,” Jackson said. “If you told me when my daughter was in kindergarten or first grade that she would be going to college on a scholarship, majoring in biology and becoming an artist, I would tell you were absolutely crazy because it didn’t look like it was in the cards for her. But I think it was because of my tenacity and my commitment to her.”

Even though Jackson had spent over 31 years as an elementary school teacher with a focus in special education, it was still difficult to get proper services, she said.

It was often a struggle over which testing to use, how data was shared, changes in IEP goals without her consent or a school official rolling their eyes when she spoke, she said.

“I was lucky because I have a strong background in educational law, and I was able to move some mountains that there’s no way parents who didn’t have that background could move, but it still was quite a battlefield for us,” Jackson said. “The squeaky wheel gets the grease, so if you don’t have time, you don’t have the money, you don’t have the energy, you don’t have the know-how, or you don’t have the wherewithal, then your kid gets pushed to the back.”

Enfield Public Schools did not respond to requests for comment.

‘It’s not surprising’

With nearly 17% of public school students, or around 82,700 children in Connecticut, identified as students with disabilities, the “battle” experience and feelings of disenfranchisement aren’t unique to just a few parents.

Cotto and Jackson may be some of the luckier families. Not every parent is well-versed in what to expect from the special education system, and many go into meetings trusting the experts in the room, only to find themselves disappointed.

“Parents for a certain amount of time go to the school team and say, ‘I think there’s something that’s not right. I think there’s an issue with my child and they’re not learning the way they should.’ And initially, they’re often told everything’s fine. ‘Don’t worry about it. Everyone develops at a different rate.’ … There is an initial tendency to just blindly trust what they are hearing from the educators,” said Diane Willcutts, the director at Education Advocacy and member of the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates. “Then, they finally can’t do that because reality is not matching up with what they’re being told.”

By the time an advocate or lawyer gets involved, trust between the parent and district is already broken from things like seeing a child regress in school, after being told that they’re doing well. Often, meaningful data is either unavailable or given without the proper context to interpret it.

It’s also common to see immigrant parents without proper translators, several advocates and lawyers said, noting that Black, Latino and low-income parents are disproportionately spoken down to, spoken over, threatened with calls to DCF or ignored.

“I have a client that was very deeply disrespected and impacted at a PPT. She’s 82 years old,” Scheinberg-Meyer said. “The person who was writing the PPT kept talking over her, kept trying to shut her up. It was very blatant.”

Scheinberg-Meyer, who’s spent most of her career working in urban settings like Bridgeport and New Haven, said she’s also seen districts disproportionately disregard parents of color “in subtle ways … by giving the impression that parents are not doing their part.”

Sometimes districts say things like “the parent is disorganized, the parent is not responsive,” Scheinberg-Meyer said. “But I believe it comes from a place of bias — painting a mother, who is a person of color, in this light of ‘you’re not doing enough,’ ‘you’re not following through,'” even if the parent is engaged.

Bridgeport, the state’s largest public school district with nearly 20,000 students, 92% of whom are students of color, provides special education services to roughly 4,000 children.

The district says that the services a child receives is determined by a "team of individuals knowledgeable about the student including the parents," and when conflicts arise, they use a "collaborative process."

"This process includes convening a planning and placement team meeting to provide an opportunity for parents and the school team to meet and share perceptions, concerns and suggestions," Albert Sackey, Bridgeport's assistant superintendent for comprehensive health and student affairs, said.

Sackey said the district's "primary goal is to provide a student with the services and supports the student needs to receive a free and appropriate public education."

"District recommendations are anchored in meeting individual students' needs based on current levels of performance and results from evaluations. The PPT meeting is a collaborative process, and by assuring parents have meaningful participation in discussions, the team can engage in conversations regarding service options for the student," Sackey said.

What next?

Earlier this month, the state legislature passed an omnibus education bill that tackled a handful of issues pertaining to teacher certification, mandated reporting requirements and other issues.

A section of House Bill 5436 will now require school boards to give families at least five days' notice before PPT meetings where the notice must "include the specific rights the law provides parents, guardians, and students at these meetings. These include the right to be present at and participate in all portions of the meeting where an educational program for the student is developed, reviewed, or revised; and have advisors of the person’s own choosing, the paraeducator assigned to the student, the birth-to-three coordinator, if any, and a language interpreter, if needed," according to language in the bill, which was sent to Gov. Ned Lamont's desk for his signature.

It's a step toward more transparency.

Parents and professionals also acknowledge that districts are often strapped for financial and staffing resources, and more transparency on that front would go far as well.

"What I will find is when districts are transparent with parents, even when the district does say, 'Yeah, we don't have that resource right now, but we're working on it,' the families are typically willing to meet the district more than halfway," Willcutts said. "If [districts] say, 'Yes, we dropped the ball, and we're going to try to make it right,' — in those situations ... they're rare, but I have been in those situations, you can almost feel the sigh of relief from families."

Other suggestions to improve the system include better training for both parents and administrators, beyond what existing partnerships may be doing.

The state Department of Education said it partners with the Connecticut Parent Advocacy Center to "provide programs to support both families and school districts that are having challenges and/or disagreements within the special education process," which includes training and seminars.

"In addition to training/seminars, there are other strategies that are known to reduce conflict within the process, such as Student Led PPT Meetings and IEP Facilitation," a spokesperson from the department said. "Connecticut has been very successful in resolving disputes between school districts and parents through the mediation process, when compared to other states."

Feinstein and Rabinowitz, who both serve as co-chairs to a Special Education Task Force that was formed from legislation in 2021, want to further that work.

"I think a substantial proportion of the conflicts in special ed are just a result of poor communication," Feinstein said. "What I've been trying to get some action on is actually doing some joint training — to have school officials work through how to best communicate with parents. ... There's a huge opportunity here, to bring parents and advocates together ... and talk about how you can get somebody to listen with respect to the point of view of somebody else."

The task force is responsible for studying issues with the cost of special education and "the criteria and manner by which school districts are identifying students who require special education and related services, including whether school districts are over-identifying or under-identifying such students and the causes and reasons for such over-identification and under-identification," according to law. They're expected to report findings later this year and present recommendations to the legislature in January.

"I understand how parents may be feeling that we're not meeting their children's needs in the best way possible. I think we need to listen to them, and then hopefully, have it be a two-way street and let them understand what we're seeing," Rabinowitz said. "It's being able to take feedback and give feedback — and that's all about relationships."