The second in a series. The first piece was an inside look at teacher evaluations. The last piece focused on the education’s revolving door.

As a college student, his proficiency in mathematics once put him on a path toward a career as an actuary, but Kevin Liner turned his skills instead to a job teaching algebra, trigonometry and pre-calculus.

By all accounts, Liner, 26, is a rising star, the kind of young talent school officials hope to attract from a pool of top college graduates who often seek more lucrative careers instead of a profession that, in the view of some, is undervalued and under fire.

Robert A. Frahm / Special to the Mirror

Math teacher Kevin Liner works with students in a trigonometry class at the Metropolitan Learning Center in Bloomfield.

“Teaching is a hard job…[but] in the public perception, it’s often not considered a rigorous job or a prestigious job,” said Liner, now in his third year at the Metropolitan Learning Center, a regional public magnet school in Bloomfield.

“I had the same misconceptions many people have about teaching. … [I was] so wrong. You find out very quickly … the amount of work that it is,” said Liner, a magna cum laude University of Connecticut graduate who was once in UConn’s business school and did internships at leading financial services and insurance companies before deciding on a teaching career.

“You always want to get better, do more for the kids. … I love teaching,” he said. “That’s why I’m doing this.”

Some critics contend that U.S. schools are losing too many top graduates to law, medicine or other high-profile careers at a time when schools are under pressure to close the achievement gap and raise standards. Educators in Connecticut and elsewhere are looking for ways to lure the brightest candidates into the classroom.

CPRE Report — Seven Trends: The Transformation of the Teaching Force

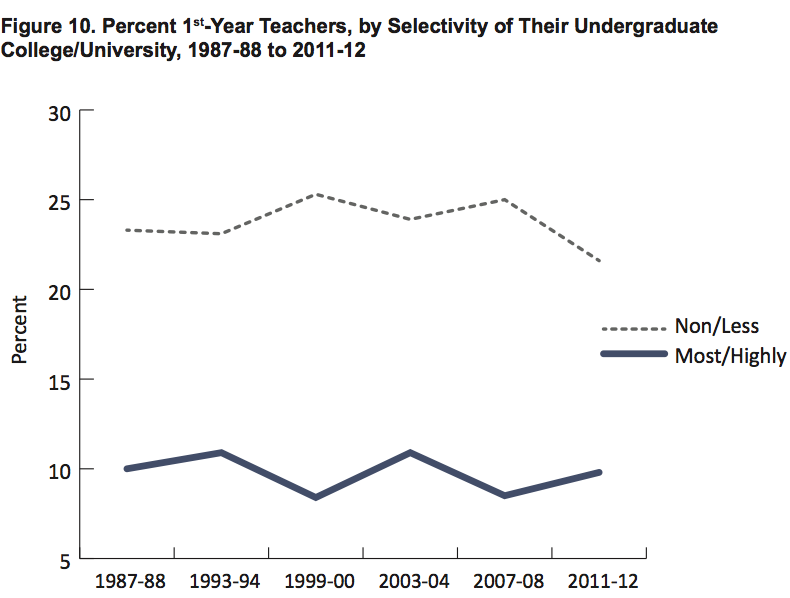

A recent report shows that only about 10 percent of first-year teachers in the U.S. graduate from a highly selective school — a number that has been relatively static the past 25 years.

“There’s no question we want to ensure we are attracting the top talent,” said Sarah Barzee, chief talent officer for the State Department of Education and co-chair of a state committee seeking to reform Connecticut’s system for recruiting and training prospective teachers. Connecticut also is one of seven states selected last year by the Council of Chief State School Officers to win a two-year pilot grant to transform those programs.

Finding the best talent is increasingly important as schools seek to replace a wave of retirements of aging teachers from the Baby Boom generation.

Still, the effort to recruit talented candidates faces obstacles.

“Many college graduates don’t have the teaching profession on their radar,” said Brad Jupp, senior program adviser with the U.S. Department of Education, part of a coalition of public and private groups last fall that launched TEACH, a marketing campaign aimed at recruiting top college graduates into teaching careers.

In a newly updated study, the Consortium for Policy Research in Education, a leading national research organization, said that only about one-tenth of newly hired first-year teachers come from the most competitive colleges, and that students majoring in education tend to have among the lowest average scores on SAT college entrance exams.

Similarly, a 2010 report by the global consulting firm McKinsey & Co. said the caliber of the U.S. teaching force lags behind that of nations such as Singapore, Finland and South Korea, where top students are aggressively recruited for teaching careers. The report concluded that fewer than one in four new U.S. teachers came from the top-third of their college classes, based on figures in a government study. In high-poverty schools, the number was about one in seven.

Teaching often suffers from perceptions about job satisfaction and prestige, but a major deterrent to prospective teachers is pay, according to the McKinsey report.

Joseph Cirasuolo, executive director of the Connecticut Association of Public School Superintendents, said, “I think young people are saying if there is something else I can do that I find satisfying and gives me noticeably more money than teaching, I’ll go in that direction.”

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the average annual teaching salary in the U.S. ranges from $52,840 for kindergarten teachers to $58,260 for high school teachers.

By comparison, the U.S. average for registered nurses is $68,910, for chemists $77,740, physical therapists $82,180, and electrical engineers $93,380. For actuaries, a career Liner once considered seriously, the figure is $107,740. Cirasuolo noted that all of those occupations require backgrounds in science or math, two areas where schools often face a shortage of top-notch teaching candidates.

Connecticut has one of the highest average teacher salaries in the nation, $69,397, ranking behind only New York, Massachusetts and the District of Columbia, according to a survey by the National Education Association.

Salary, however, was not the key factor in Liner’s decision to teach. “I knew the numbers going in,” said Liner, who started at $49,639 and now makes $55,451 annually. “I have no regrets at all.”

At Metropolitan Learning Center, Principal Sasha Douglas said Liner engages students in lessons that have real-world applications. In one recent lesson on exponential functions, Liner challenged an algebra class to chart the potential return on two separate investments, asking one group of students to defend one investment as the better choice and another group to argue for the other, using interest rates and other data to determine returns.

Douglas said Liner is an “ideal example of the type of beginning teacher that we want to attract.”

Robert A. Frahm / Special to the Mirror

Still, as a young college student, Liner wasn’t sure at first whether teaching was for him.

“He was asking tough questions about schools and teaching and why would anyone want to do this. … questioning whether his career path would fulfill him more in teaching or in an actuarial career,” said professor René Roselle, who worked with Liner in UConn’s teacher preparation program.

Liner said it was during undergraduate internships at the ING financial services firm and the Prudential insurance company that he began thinking about other possibilities. “I enjoyed the projects I worked on, but I think I wanted to be more involved with the human piece,” he said.

He entered UConn’s five-year Integrated Bachelor’s/Master’s teacher preparation program, pursuing a dual degree in mathematics and education. In his senior year, a student teaching assignment at Windham High School became a turning point, he said.

“Once I got into a classroom, I was sold immediately,” he said. “That’s what I wanted to do … I enjoyed building a relationship with the kids.”

Roselle said, “I think he felt spending time behind a desk with numbers wasn’t as exciting as spending his life in front of a class of students.”

Liner, who grew up in East Hartford, said his experience at Windham and later as a graduate student intern at Hartford’s Bulkeley High School convinced him that he wanted to work with students from urban and low-income areas. He said he was influenced “by the inequities I saw in urban districts. … That was a critical moment for me.” At Bulkeley, working under Roselle’s supervision, he helped develop a senior year project for students potentially interested in teaching careers.

He also co-authored with Roselle a research paper on student teachers’ perceptions of urban schools that was published in the academic Journal of Urban Learning, Teaching and Research.

Liner’s stellar college background put him on the radar of Anne McKernan, who was then principal at Metropolitan Learning Center. “I called my connections at UConn and asked who were their top students,” said McKernan, who hired Liner.

McKernan, now the chief academic officer for Enfield Public Schools, said she was impressed not only by his intellect, but by qualities such as “grit, persistence and determination.” To be a great teacher, “you need passion and personal skills,” she said.

As state officials re-examine teacher preparation programs, one possibility is to make those programs more selective.

A 2012 report by the American Federation of Teachers said the quality of teacher preparation programs varies widely, and that the preparation system in the United States is “at best confusing and at worst a fragmented and bureaucratic tangle of stakeholder groups….”

The report said teaching “must raise standards for entry into the profession through a process similar to the bar process in law or the board process in medicine.”

There have been efforts over the past two decades to find top candidates outside of traditional teacher preparation institutions. Programs such as Teach for America and TNTP (The New Teacher Project) are highly selective, recruiting talented college graduates or career-switching professionals to work in some of the nation’s poorest and most challenging schools. However, some in the education establishment have criticized those programs, contending the short training period for new recruits is inadequate.

In Connecticut, officials are discussing raising standards for entry into teacher preparation programs. Current state regulations require a minimum B minus or 2.7 grade-point average for admission to traditional training programs. A handful of nontraditional programs, including the state’s fast-track Alternate Route to Certification program and the Teach for America program, require a 3.0 GPA. Prospective teachers also must pass certification exams testing subject knowledge.

Nevertheless, school district recruiters often are looking for more than just top grade-point averages or high scores on SAT college entrance exams.

“I think there are intangibles not measurable in a college transcript,” Colin McNamara, an assistant superintendent for Wallingford Public Schools, said during a recent job fair at UConn. “I’ve seen students graduate with a 4.0 [GPA] and can talk to you about theory, but you put them in front of a class of 25 kids, [and] it’s a train wreck.”

Personality traits are crucial in assessing talent, he said. “Is this somebody I’d want to put in a classroom in front of my own children? Would they be able to keep them engaged?”

Representatives of more than 40 school districts attended the job fair, seeking to recruit new teachers from students finishing preparation work at UConn’s Neag School of Education – a program that earned high marks from several of the recruiters.

“We’re looking for the best of the best,” said Thomas McMorran, principal at Joel Barlow High School in Redding. “We want to see if a person has a genuine love of the subject area and a real desire to work with kids. Those will be the people we will interview.”

Robert A. Frahm / Special to the Mirror

UConn graduate student Allison Zimmermann, left, meets Colchester Elementary School Principal Anne Watson at a job fair for prospective teachers.

Several recruiters cited concerns about growing demands on schools as a factor discouraging some top students from choosing teaching careers. In Connecticut, for example, teachers are under pressure to adapt to challenges such as rigorous new Common Core academic standards and the switch to a new statewide student testing program. In Connecticut and elsewhere, many teachers have complained openly about controversial new evaluation systems that rate educators in part on student test scores.

“The pendulum in education swings so often,” said Christopher Bennett, principal of the William J. Johnston Middle School in Colchester. “There is so much negativity right now. I think that hurts the profession,” he said.

Nevertheless, Bennett was optimistic about finding top recruits at the job fair.

Candidates such as 22-year-old Allison Zimmermann seemed eager to tackle the challenges of the profession.

“I’ve actually had people try to convince me not to teach, [but] I’ve always wanted to be a teacher. I’ve had people say, ‘Why didn’t you go into accounting?’” said Zimmermann, a magna cum laude UConn graduate from Glastonbury. “I have a passion for teaching.

“To me, the money is not that important,” she said. “I can’t imagine sitting in a cubicle. It’s not for me.”

At the Metropolitan Learning Center, Kevin Liner expressed the same sentiment, saying the connection with students is what drives him.

Getting that message to other top students is the challenge, he said.

“When people realize the effect they can have on other people and the positive changes they can make, the profession is extremely desirable. The benefit I get day to day from this job is unbelievable.” ♦