Rebecca French is blunt when she’s asked about hurricanes and Connecticut’s preparedness for them.

“Have we figured out as a state, as a region, individually figured out how to not have damage from those storms? No!” she said.

French ought to know.

Until recently, she was with the Connecticut Institute for Resilience and Climate Adaptation (CIRCA) – a joint government and University of Connecticut research and funding clearinghouse formed in the aftermath of Irene and Sandy. French now directs the implementation of two federal grant programs that are providing a small amount of money to Connecticut for climate resiliency projects, chiefly in Bridgeport.

“I don’t know that it’s realistic to say we’ll never have damage from a hurricane,” she said, noting that the financial cost of ensuring there is no damage is prohibitive. Managing risk and learning to live with water is more practical and affordable.

“I don’t think the vision for Connecticut is we will never sustain damage from a storm,” she added. “The vision is you recover as quickly as possible.”

This is the second in a two-part series. Click below to read part one: Connecticut’s vanishing shoreline: One storm away from disaster

But whether the state is significantly closer to even that is doubtful. A quirk of Connecticut government as a home-rule state means the state has only limited authority to supersede local governments. Individual cities and towns handle their own zoning and development regulation and that mostly – though not entirely – puts resiliency matters in the hands of local governments.

With finances tight and local budgets reliant on high-tax shoreline properties, the idea of changing anything that would decrease property tax revenue is nothing short of municipal poison.

“Most of these communities have been making decisions about what goes where for about 350 years. This is going to take decades and decades to unwind or to change the path and change the mindset,” said Adam Whelchel, science director for the Nature Conservancy’s Connecticut office who has also advised many of the state’s shoreline communities on sea level rise adaptation.

He believes changing the mindset could take a lesson as devastating as the 1938 Category 3 hurricane that decimated shoreline towns and caused such severe interior flooding that it is still considered the worst natural disaster in Connecticut history.

“If we had a big reset like that, I think you would see some serious, more deliberate, more permanent types of steps that would actually move structures out of harm’s way.”

In the meantime Whelchel and others are willing to live with baby steps – a bioswale here, a tide gate there. “It’s something. It’s moving.”

“Policy wise at the state level, things have moved slowly,” said Leah Lopez-Schmalz, chief program officer of Connecticut Fund for the Environment. “But the idea of shoreline resiliency has become an issue for legislators. I wouldn’t have predicted that.”

She pointed to the creation of CIRCA and the little bits of legislation that have gone through. “I’d say that the state has really started some of the major steps that are needed and I think were really wise.”

A resiliency planning survey conducted for CIRCA by the University of Connecticut’s Center for Land Use Education and Research and Connecticut Sea Grant of 20 shoreline communities affected by Sandy determined their biggest concern is flooding.

“Whether it’s from coastal storms or heavy precipitation events, flooding is clearly the number one issue in communities,” said Juliana Barrett, a UConn extension educator with Sea Grant who worked on the survey and who has advised coastal communities on resiliency.

But she found communities essentially are paralyzed by a combination of factors – the daunting finding by CIRCA that sea level rise is likely to increase 20 inches by 2050, the cost of remediation, and the lack of expertise in most municipalities.

“The politics and the state of the budget,” she said is what she hears from local officials: “’There’s no money for it, so what can we possibly do within my four-year term?’ That’s not to say that communities aren’t moving forward.”

The state received a little more than $159 million in Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) funds from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development for resiliency projects in shoreline areas affected by Sandy – more than a dozen communities.

Most of it went to home rebuilding not covered by FEMA. About a quarter of it went to infrastructure repair and resilience. But it was all used to rebuild more or less where structures existed originally – theoretically stronger than they were before, but generally in the same location. Many view that as a failure of federal policy that essentially assumes federal liability for keeping structures in vulnerable locations.

Bridgeport is changing that dynamic a little, using additional federal funding to help make a few fundamental changes — emphasis on few and, in the scheme of things, not very much funding.

Resilient Bridgeport

Bridgeport received awards in two national resiliency competitions – now combined into a project the city calls Resilient Bridgeport. But at $10 million for one and $42.5 million for the other, those efforts will not come anywhere close to achieving the goal of reimagining Bridgeport as a genuinely climate change-resilient city.

This vastly scaled back plan focuses on the city’s south end, a lower income area that took the brunt of the flooding and damage in Irene and Sandy. Key components of the plan are to raise University Avenue by 12 feet in some locations, build a berm to protect the immediate shore area (including the rail corridor), and to create a so-called resilience hub as a staging area for disaster response, including providing amenities like charging stations.

There have been community meetings and other forms of outreach for three years to get everyone on board with the concept. But while the money is committed, only about $5.5 million has been allocated so far to pay the design team, and basically nothing structural has started and probably won’t until 2020.

“I think if a new storm comes in within the next two years or so, no I don’t think anything has changed,” said David Kooris of the state Department of Economic Development, who was Bridgeport’s director of planning and economic development when the storms hit.

Until recently Kooris was the point-person in the state Department of Housing overseeing implementation of the two competitive awards – the position now held by French – as well as coordinating State Agencies for Resilience (SAFR, pronounced safer), an inter-agency climate resilience strategy, which he sill handles.

The Resilient Bridgeport project – despite the many design firms that have worked on it – is still generally referred to as “David’s plan,” throughout Bridgeport.

“I think the biggest thing that’s changed is, prior to the storms if we had been talking about this type of infrastructure, we would have had a hard time getting people to meetings and there would have been a lack of tolerance for the type of impact in their neighborhoods that infrastructure we’re talking about would create,” Kooris said.

Elizabeth Torres, executive director of Bridgeport Neighborhood Trust, said the design team and government officials did an “awesome job” communicating with south end residents.

“I felt like my voice has been heard,” she said. “To say that the community is excited about Resilient Bridgeport would be an understatement.”

Lydia Silvas, who lives in Seaside Village, a housing project that regularly faces flooding, and not just during storms, was skeptical of the plans. “I think it’s going to be a Band-Aid truthfully,” she said. “Eighty years from now it’s going to be wet, real wet, around here.”

Kooris points to I-95 and the rail line as areas that, while facing hazards from climate change and sea level rise, are not really movable. But Avangrid, an electric-gas utility company, is moving two substations farther inland – an action often described as impossible and too expensive.

The University of Bridgeport is also moving its athletic facilities to a more vulnerable area closer to the water now occupied by the Health Sciences building, which will move to a safer place where the athletic area is now. The athletic area will become the expendable part of the campus.

The goal, many people involved in the Bridgeport work point out, is to make even the small projects the city does now, further adaptable long term, remembering that no so-called resilience is foolproof let alone permanent.

“Adaptation is an incremental process that allows people to get their minds around the problem,” said David Waggonner, a founder of Waggonner and Ball Architects in New Orleans. He’s been involved in resilience planning all over the world including New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and is working with Bridgeport on the current resilience plans.

“The thing that has to be broken is the idea that we can engineer our way out of this,” said Waggonner, who worked with the city going back to the first competition after Irene. “You’re always managing risk.”

Nothing for New Haven, but…

The state also applied for money for New Haven through the same project in which Bridgeport is participating. In fact, the state applied for even more money for New Haven – nearly $59 million.

And what did New Haven get? Nothing, zippo, nada.

But you’d never know that. As part of its Climate and Sustainability Framework unveiled in January, the city is moving ahead on all kinds of projects anyway – faster than Bridgeport.

The federal money sought for New Haven had been targeted for a new pumping station – a $40-$60 million investment – to deal with the largest of the city’s problems, which is how to get water out of low-lying areas, especially in the face of sea level rise-induced nuisance flooding that is growing more frequent. The Long Wharf area, including – most critically – the rail yards, built on 200 acres of fill where New Haven’s harbor was once located, faces that kind of flooding routinely now. (Read about that here and here.)

When that plan fell through due to lack of federal funds, the city found a work-around solution. It is installing more than 300 bioswales – about two-thirds of them downtown. These innocuous looking 5-by-15-foot, five-foot deep rain gardens use the area’s sandy soil to soak up runoff.

While the bioswales might not eliminate the need for a new pumping station, they’re likely to help the city get away with building a much smaller one, said Giovanni Zinn, the city’s engineer.

“We’re leveraging the way nature does things over millions of years, not trying to bend nature to the will of man,” Zinn said. “The big philosophical shift we’ve had since Irene and Sandy is you really have to rethink the shoreline. Even the term itself – if you think shoreline – a line – it’s really an area – it moves, it creeps, it erodes.”

That philosophical shift is apparent in multiple projects in New Haven.

Instead of the sheet pile sea wall promised to Morris Cove residents whose homes were damaged in Irene and Sandy, the city has everyone on board with a berm and additional sand as a natural barrier. It could be in place by the summer of 2019.

Living shorelines – also natural barriers that work with a shoreline’s movement – are planned for East Shore Park near Morris Cove and Long Wharf.

But the city still faces criticism for its determination to pour money into Tweed Airport, which sits in a floodplain that every sea level rise scenario shows will be underwater by the end of the century, if not sooner. Tide gates have helped some with flooding, but not entirely.

“We would much rather have a flooded runway than a flooded neighborhood,” Zinn said. “So from that point of view it works.”

The state also just spent nearly $2 million in bond funds to rebuild a fishing pier that was badly damaged by Irene before being totally destroyed by Sandy.

“We built it understanding it will get flooded and frankly it’s designed to get flooded early on in these storms so that the heaviest of the wave action is above it,” Zinn said. “I’m sure you can pick a bone with us that we shouldn’t be building that type of infrastructure in a place that gets flooded. On the other hand, do you just not simply build any more piers at all or do you build them all way high up in the air?”

The city is also likely to face criticism as it moves ahead with plans to redevelop Long Wharf into a pedestrian and commercial district. The area was underwater once and all projections are that it will be again.

Making these decisions involves finding a balance between growth and climate change, Zinn said.

“Every infrastructure discussion we have in the city is very much driven by climate change,” he said. “We’re very much concerned about climate change and resiliency, but we’re also very much concerned about providing opportunities for our residents and having economic growth.

“At this point, I don’t think it’s conceivable, given the quantity of infrastructure that is in the Long Wharf area, that it would go back to open water. Where would 95 go? We don’t see it.”

Fairfield flooding risk great

Fairfield has the dubious distinction of having the most residential real estate in Connecticut at risk from future nuisance flooding due to sea level rise, according to data released by the Union of Concerned Scientists earlier this year.

Among its many shoreline vulnerabilities is a large area of homes adjacent to Penfield Beach that is basically located in a bowl. It floods. And it did so big-time during Sandy, along with other parts of town located near several creeks, rivers and the beach – including an area perilously close to downtown.

Since then more than 100 homes in Fairfield have been elevated – and that doesn’t include the teardowns that were rebuilt at higher elevations. But with sea levels encroaching, how accessible will the roads to those houses be in the future? Along Fairfield Beach Road, some houses hang over the water at high tide even now.

And that’s how it will stay.

“There’s no retreat strategy, so to speak,” said Joe Michelangelo, Fairfield’s public works director.

Michelangelo said if a storm like Sandy were to hit the town today, streets would flood and there’d be no access to elevated structures, but the town would be able to pump out areas much faster than last time. “We’re talking half a day instead of five days,” he said.

There’d be a lot less property damage – we’d return to a sense of normalcy much quicker.”

The town is trying to push forward with a number of projects. It already has one microgrid operating for town buildings and is planning another along with a flood control barrier at the wastewater treatment plant, which sits at the edge of Pine Creek not far from where it intersects with Long Island Sound. There are plans for more tide gates, in addition to a new one that’s already installed. And the town is considering a pumping station in the Jennings Beach area, as well as a berm of some sort to protect Penfield Beach – both of which are likely to draw the ire of residents trying to protect their views and beach access.

Below: The rendering on the right is a proposal for a vegetated dune along Penfield Beach in Fairfield. It would lessen erosion, but homeowners would likely lose some of their coveted views of Long Island Sound. Click and drag arrow to see full scene.

Even if all the projects are built – will it be enough, or be completed quickly enough, to protect Fairfield?

“I think it’s almost a race against the clock,” said Laura Pulie, the town engineer. “It’s just a matter of time. Are we going to have things done in time?”

Ask Pulie, Michelangelo, and Flood and Erosion Control Board chairman Dick Dmochowski — who learned about storm flooding the hard way and elevated his own house by 6.5 feet — whether the town’s current efforts will get it to the end of century – and all the heads in the room shake “no.”

Roadblocks

Even communities genuinely trying to prepare for climate change and sea level rise encounter roadblocks. The top three – money, money and money

- Not enough in the budget.

- The potential loss of tax revenue from waterfront property.

- Reluctance to spend for projects residents may never see.

The fourth roadblock is reality versus political will — essentially the recognition that certain properties will simply no longer be usable and the willingness, or lack of it, to plan for that now.

Take Stonington. In 2015, the town used $150,000 from the big pot of Sandy funding to prepare a coastal resilience plan. It was finished about a year ago and was adopted as an appendix for town’s plan of conservation and development.

The report stated that 27 percent of the town, accounting for 53 percent of its total tax base, was at risk from a 1,000-year storm event in 2050. And while it identifies the top 25 at-risk assets, there’s no real priority list of what to do first because there’s no money to do it.

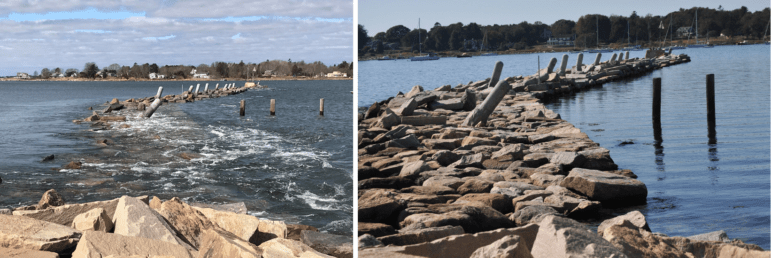

Work is planned to upgrade a breakwater in Stonington Borough. It was built in 1827 and portions of it are underwater right now at high tide, which means it’s ineffective during a storm when it’s needed.

“Now you could fix it by dropping a couple of rocks on it and maybe that works during high tide today, but wouldn’t the better solution be fixing it to meet the 30-year sea level rise time frame?” asked Jason Vincent, director of planning, rhetorically. “We will continue to seek funding from community leaders to implement the recommendations in this plan.“

But when asked whether the town will act fast enough or do enough, period, Vincent said that probably depends on whether Stonington gets hit with a catastrophic storm.

“I think the fast enough will only come with a storm that creates enough chaos, he said. “Even though there was chaos from those two storms in this town, I don’t think it created enough chaos that there’s an urgency to act.”

Guilford was among the first, if not the first, shoreline community to address climate change and sea level rise in the immediate aftermath of Irene, which swamped its coastal areas – especially the salt marshes that had been filled and developed.

Working with the Nature Conservancy and Yale, the town developed a radical approach that opted for letting some of the most vulnerable areas go over time, eventually removing structures and retreating. The plan was approved, but not much has been done since then.

Three small roads were elevated and there have been seemingly endless discussions about what to do with Route 146 – a state road that runs through Guilford and Branford and that floods regularly.

“We’re sort of muddling through with that project,” said George Kral, Guilford’s planning director.

While there was pushback from residents once they realized how drastic some elements of the plan were, Kral said he didn’t see it as a doom and gloom scenario.

“It’s not some kind of crushing dystopia,” he said. “It might be a positive place to live – albeit with a lot more water. It made thinking about these things less pessimistic.

“It’s adapting to a continued desire to continue to live near water,” he added. “Of course you might have to take a boat.”

Jake Kara contributed to this story.

This story was funded in part through a grant from Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation, administered by LION Publishers.